I Was Pregnant, But I’m Not Anymore, And This Is Our Story

Trigger warning: high risk pregnancy, birth defects, abortion

“You’re pregnant? Did your doctor talk to you about taking this medication?” the pharmacist asked. “Yes, I am. But I won’t be tomorrow when I take it,” I responded.

She removed the health condition “pregnant” from the system. Earlier that day, someone else told me that she noticed my belly getting bigger. “Congrats,” she said. I thanked her and moved on.

They all didn’t know. But let’s start a few weeks earlier.

A home pregnancy test was positive. I didn’t believe it. Then the ultrasound showed a heartbeat. “That’s your baby,” the gynecologist said.

I was happy, but also worried. Will everything be all right? Will the baby be healthy? What should I eat?

Teresa Hammerl

Skin care products, no coffee, no alcohol, prenatal vitamins, enough sleep — I really wanted to do everything right, so the baby, my husband, and I could enjoy the rest of the pregnancy.

We were going to be excited about the first kicks, hiccups, maternity clothes (okay, maybe I was more excited about that than everyone else), a growing baby bump, our future, learning how to give birth, touring the birth center, and buying everything for the baby’s first months.

I also created an Instagram collection with all the cute little baby clothes I was able to find. Eva Chen’s Instagram stories (there is also a newsletter) turned out to be my go-to place for the best product recommendations. What’s the safest bassinet, the best milk pump, and the most recommended car seat?

I usually like to worry about a lot of things in my life, and soon enough I discovered that there are a lot of prenatal care tests. It’s a lot to process. What would the prenatal screening tell us?

I didn’t see arms or legs on the sonogram picture. Were they really there? Yes, they were.

I was worried about all the things that turned out to be all right. But I didn’t really think about the fact that every four and a half minutes a baby is born with a birth defect in the United States.

But after the ultrasound technician finished the first trimester ultrasound, my pregnancy turned from a low- to a high-risk pregnancy within a couple of minutes.

Teresa Hammerl

“Something doesn’t look right with your baby’s heart,” the high-risk pregnancy doctor told me.

It looks like one side of the heart didn’t form right. It usually turns out to be the left side. Congenital Heart Defects (CHD) are among the most common birth defects. About 40,000 babies in the U.S. are born with a heart defect every year.

The genetic counselor later told me that it doesn’t look like I’m in a high-risk group for chromosomal abnormalities, but I still decided to do an invasive procedure to learn more about the chromosomes of the fetus.

The test is called chorionic villus sampling (CVS), and it surprisingly doesn’t hurt as much as expected when someone sticks a needle through your abdomen to the placenta.

The doctor and a technician walked me through the whole procedure. They told me what they were going to do next, and it helped a lot to make me feel like I’m still in control — in a situation where I felt like I had lost control.

“One step at a time” was something I heard a lot over the next couple of days. Especially at that moment, I also felt very grateful to have access to health care, to prenatal care — it was a reminder how important it is for everyone.

I also learned that you can’t just eat something to make the heart grow the way it’s supposed to. You can’t just exercise more to prevent a CHD. It wasn’t my fault. It’s hard to accept that.

Then we scheduled an appointment for a fetal echocardiogram with a pediatric cardiologist. The day before the appointment, the CVS results came back. Everything was okay.

I felt relieved.

Suddenly there was hope again, but I also felt guilty for even being afraid of having a baby with a disability. It’s something I did not expect, something I wasn’t prepared for. I wasn’t sure how I could deal with it. What if the baby needed special care I couldn’t provide?

I was afraid of the unknown.

I connected with someone whose baby has a CHD. I also remembered Jimmy Kimmel’s emotional speech about his baby, who was born with a hole in its heart. I looked at Instagram pictures of his smiling son.

I also met with a social worker, and she gave me a long list with resources. I talked to my midwife. She acknowledged my situation, and I knew she would be there for me along the way. No matter what.

Also, I found out that there are a lot of support groups out there, and that it’s okay to take care of my mental health situation too. To focus on my baby’s future also means that I have to focus on my own health.

I was reminded that other expectant mothers have miscarriages, find out about birth defects, or have abortions. We go through long periods of disappointment and grief without talking about it in public. One reason why I decided to publish my story is that I hope someone in a similar situation might feel less alone.

I was wondering if we should name the baby Lev, as I read somewhere that a family named their baby with a CHD after the Hebrew word for heart. I liked that idea.

When the day of the echocardiogram came I felt nervous, but also hopeful. Maybe it wouldn’t be as bad as we thought. Maybe we would have to spend a lot of time at the hospital, but that would be okay. If I couldn’t breastfeed, there would be a lactation consultant to talk about options.

If our grandparents in Europe couldn’t see the baby for the first couple of months, we would just do a lot of Skype calls. Our parents could visit us. They could support us. We were lucky because I was sure we could also somehow be able to afford a nanny to help us.

My husband and I could work from home. We would have a support system. We would all figure it out. I tried to convince myself that it would be fine. It would work out.

“Teresa,” the ultrasound technologist said, when she called us to the echocardiogram.

She took many different pictures of the heart, I tried to look away. I’m not the pediatric cardiologist, I kept telling myself. Then the real cardiologist came in. She took even more pictures. I thought that was okay. I didn’t ask questions. I knew that she would explain everything once she was done. Then she said “Let’s go to another room, so we can talk.”

We sat down.

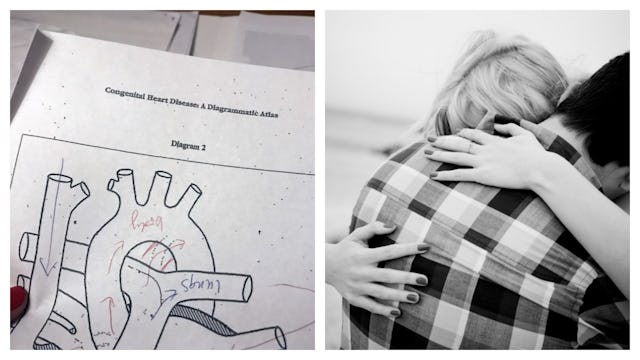

I looked at her, and before she even began to speak, I knew it was over. She started to draw a heart. “That’s what a normal heart looks like,” she said. The baby is missing a large part of the left side of the heart. We talked about hypoplastic left heart syndrome, considered a severe birth defect.

cdc

She was holding a folder with more detailed information about fetal abnormalities in her hands.

Whatever we decided to do next, it would be our decision as a family to choose which way we wanted to go. Nobody else could make that decision for us. We learned that other families, other expectant mothers, choose to continue the pregnancy while others don’t.

We then talked about a heart transplant, about three surgeries the baby would have to go through after it was born. Our child might live for 30 years, but it was hard to say. Nobody would be able to tell us if she or he would be able to make it through the first few months and years.

Having a baby with a CHD is often an “isolated incident,” a chance of having another baby with a heart defect is considered to be low. I felt like I didn’t want to talk about it. I cried a bit.

We did talk a lot about our options before, so I knew what we would be doing. I knew what I wanted.

The next day we scheduled a D&E procedure, a surgical abortion performed at the hospital. I didn’t have any doubts about doing it, but I still wanted to make sure to give myself one more night to think about it.

The abortion was done a little less than one week later. I spent seven hours at the hospital that day, but I didn’t have to stay overnight. I was allowed to eat a light meal, and I drank some water.

The procedure itself took less than an hour. The rest of the day we waited for the cervix to dilate. I was awake the whole time.

The abortion didn’t hurt. I just felt a bit of pressure. I also felt incredibly grateful to live in a place where no one questioned the decision I made. I was given room to talk about my mental health situation and if anyone had forced me to me to do something.

I felt respected as a woman, as a human being. I was also grateful to be in a teaching hospital, so a resident was able to learn and gain more experience.

I didn’t feel sad afterwards. I expected to feel tired, disappointed, or hopeless. I felt relieved. It’s hard not to feel guilty about that.

I was also given instructions on how to take care of myself after the procedure and what I should pay attention to, and I was told that everyone reacts differently and that it was nothing to worry about.

For now, I’m still thinking about all the medical professionals like receptionists, technicians, nurses, genetic counselors, a midwife, a social worker, and doctors I met along the way.

I couldn’t have gone through all of this without them.

This article was originally published on