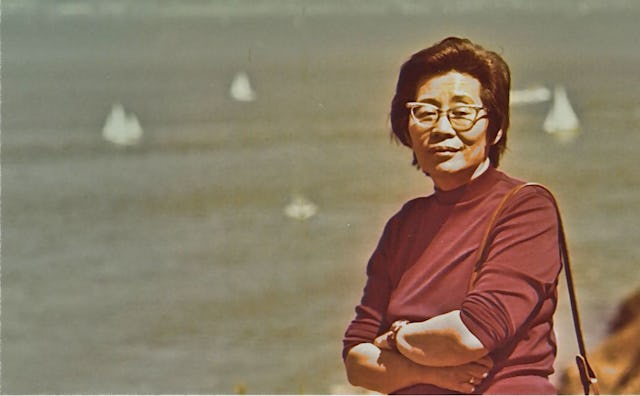

Chinese in the Mississippi Delta: My Grandma's Life

We left the church and drove the two short blocks to my grandmother’s house on Elm Street. It was dark and late. My brother pulled into the driveway and trained his rental car headlights on the front door. My mom and I stood in the glare while my husband, Brian, fumbled with the key my uncle had given him at the fellowship dinner in the church basement after the funeral. To the left of the door, the screened-in front porch hung limply from the side of the house. The fine mesh was ripped and bent in, and wooden planks of the porch floor had rotted away completely. We could see leaves and dirt below through the large holes.

We stepped inside, reminding each other which lights were safe to turn on, which ones my uncle had told us to avoid because the wiring was too old and frayed. It was January 2004 in Marks, Mississippi, and the air in the house was cool and a little damp, prickling with mildew. My grandmother—Por Por, we called her, using the Cantonese—had spent most of the last decade away from here, rotating among her children’s houses for months at a time. But the small, one-story wood-frame with a pitched roof and towering tree out front, where Por Por had lived for 60 or so years, was still at the gravitational center of the family. It was the house my mother left behind when she moved away to New York City, the house where we spent Christmases when I was a kid, six or eight cousins piled up on the floor at night. Nothing about it had changed.

© Jen Shotz

Dr. Phil Isn’t a Real Doctor

Por Por would have pretended to scold her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, ranging in age from seven to 37, if she’d seen us huddling together at her coffin to slip handwritten notes, a small piece of jade, a pecan tart, and a crayoned one-way ticket to heaven down the side of the soft satin cushioning. She would have scrunched up her face, still smooth at 87, and puckered her lips at me—her version of “Oh, shush,”—if she had known I would stay up all night writing four single-spaced pages about her to read at her funeral. She would have waved me away with her soft hand if I’d told her it was harder to write four pages than 40.

I tried to tell the truth about her, and I don’t think she would have minded. There were the flat and glowing descriptors, of course: She was the kind-hearted churchgoer, the lady who baked pecan tarts for church functions and birthday cakes for neighborhood kids in the design of their favorite superheroes. A devoted friend who still wrote regular letters to the pen pal she’d been corresponding with since she was nine. Best grandma ever. Sunday school teacher. Thoughtful neighbor.

She would have been proud of that list, but I think she would also have giggled, secretly pleased, to hear me tell the packed First Baptist Church deep in the reddest of states that she was, in fact, a raging liberal who sent me regular emails filled with typos and random slashes, written in all caps, saying “DUBYA IS AN IDIOT. THESE STUPID MEN ARE SENDING THIS COUNTRY STRAIGHT DOWN.” It was a part of her that she would never have put on display, not there, not while she was alive.

There was so much more, though, that I didn’t say. I would have loved to tell all the cousins and church friends and even the mayor of Marks, stuffed together into the wooden pews, everything about her. I would have loved to have given her what she always wanted, what we all want: the chance to be known. I would have told them she was still angry at my grandfather Gung Gung for some amorphous grievance, even 33 years after his death, and frustrated trying to figure out her place in the busy lives of her grown children.

Por Por and I argued often. I pushed her to tell people how she really felt; she pushed me to be kinder.

That she was confused by the emotional limitations imposed by the time and place in which she was raised—strangely suspended in the sadness and loss she felt as a 10-year-old, when first her mother and then her grandmother died, but lacking the vocabulary to say that. She was still the young mother who not only lost her firstborn son when she was just 34 and he was 12, but who also lost some irretrievable connection to her other children on that day.

I wanted every person in the room to see her like I had seen her. Por Por and I argued often. I pushed her to tell people how she really felt; she pushed me to be kinder. I tried to teach her to stand up for herself; she tried to teach me to back down. I told her Dr. Phil wasn’t a real doctor, and she told me she didn’t care. I rolled my eyes at her, and she just grinned at me.

Not everyone can say this about their grandma—and not everyone has their grandma until they’re 34—but she was my person, and I was hers. We looked out for each other, always. When she was in her 70s, I nicknamed her “Grambo,” because she was unconquerable. I stood above her coffin and read from the neatly typed lines on the page, and I remembered all the times she had told me I was the only one who really understood her. For so many years, I had delighted in that prize, hoarded it even, but now I wanted to force everyone else to share the blessing, and the burden, with me.

The Poorest County in the United States

Por Por moved to Marks—population aspiring to 1,500—in 1935 from Chicago’s Chinatown to start her married life with Gung Gung. Family legend has it that when Por Por arrived, the entire town came out to see her at the small shack of a train station. She often told me it wasn’t just geography that separated her from her old life—the Chinese girl from the big city. She was 20.

© Wing Family

Marks is the seat of Quitman County. Reportedly, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited the town in 1966 and witnessed a teacher dividing four apples and one box of crackers among a classful of impoverished students, feeding them lunch for the day. He was brought to tears. In 1968, the year my mom gave birth to my older brother in Los Angeles, Dr. King returned to Marks in the first stages of his Poor People’s Campaign to fight poverty and racism. In a speech delivered just days before his assassination, he spoke of “Quitman County, which I understand is the poorest county in the United States.” A little over a month after his death, a symbolic mule train left Marks and made the trek to Washington, D.C.

© Jen Shotz

It was unlikely, perhaps, that Por Por would leave her urban life to settle in the rural south. It wasn’t an easy transition: She went from streetcars to dirt roads, from a city of a million people to former plantation lands. Chicago had its fair share of racial tension—she used to tell me that Chinatown and Little Italy were adjacent to each other there, and the Chinese and the Italians would stand on opposite corners and call each other names—but in Mississippi, it was a deep and ugly wound. She adapted, though, because she had a community.

There were lots of Chinese families rooted in the Delta—a surprisingly sensible migration that started during Reconstruction, after the demise of plantation commissaries. Chinese immigrants, seeing an opportunity, shunned the hard labor white folks expected them to do and, instead, opened grocery stores that served black customers. My grandfather was one of them. He came from China, alone, when he was 14, joined cousins in Marks and later opened Wing’s Grocery Store.

© Jen Shotz

I had been visiting Marks from Los Angeles since I was little, and the squat houses, dry, dun-colored lawns, and sagging Main Street, with its short block of empty or sparsely merchandised stores, were familiar but still surprising. There was no getting used to the shanties with paper-covered windows and no electricity, where people really lived. Marks never failed to remind me of a back-lot set of a southern town, complete with character actors in costume.

On a trip to Marks when we were young, my brother and I stepped into the dimly lit drugstore for a few things. The pharmacist looked us over, paused, looked us over again, and said, slowly, “You must be some of the Wings. Are you Virginia Faye’s kids?” At the time, my mother, Virginia Faye, had not lived there for more than 30 years. On the one hand, it wasn’t hard to peg us as “some of the Wings.” We appeared at least partly Chinese, which we are, and the Wings were one of a handful of Chinese families in Marks. But the fact that he knew both that we were Wings, not Pangs or any of the others, and which Wings, speaks to the nature of the town itself. He assessed our genders and age spread, did a quick calculation, and figured us for Virginia Faye’s kids. That’s small-town math, something we didn’t have back home in California.

When my mother was a girl, this was a town of separate water fountains, separate schools. She remembers old black men stepping off the curb when she walked down the sidewalk, tipping their hats as she passed. Then, as now, the only way in or out was on flat highways lined with cotton fields, stray white tufts clinging to the edges of the asphalt.

In Marks, whether it was superficial or not—something that can’t ever really be quantified—the Chinese were accepted.

Por Por and Gung Gung raised six children and ran the grocery, just on the corner of Main Street where “colored town,” as they called it then, began. Eventually, they moved from an apartment behind their store to the Elm Street house, on the white side of town.

Being Chinese gave them a meager foothold just above being black in the segregated south. Maybe because they always had someone beneath them on the social strata, or maybe because the town was an outpost of relative tolerance, my grandparents and their family were well-respected and successful. Over the years, their aunts and uncles and cousins were mayors, employers, landowners, homeowners and businessmen. In nearby towns, Chinese kids were expelled from white schools and forced to build their own or move away. But in Marks, whether it was superficial or not—something that can’t ever really be quantified—the Chinese were accepted.

© Wing Family

Rodgers and Hammerstein: A Great Chinese Tradition

The night before Por Por’s funeral, our extended family—including my mom, her four surviving brothers and sisters, and all eight of us grandkids with our spouses and children—took over a Comfort Inn in Clarksdale, the “big” town just 18 miles to the west, and commandeered the function room. The cousins from Clarksdale laid out catering trays of homemade soy sauce chicken and barbecued pulled pork, strawberry trifle and reddish-brown chocolate cakes.

We folded funeral programs on the buffet—Por Por once told my mom she wanted us to sing the hymn “How Great Thou Art” and “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” a song from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel, at her funeral. We set up stations at breakfast tables and formed assembly lines to stuff nickels and coffee-flavored candies into small white envelopes to pass out at the cemetery—a Chinese tradition: a sweet to take away the sadness, and money for luck.

RELATED: 14 Funeral Songs To Help Honor A Late Loved One

We pulled pictures from our purses and luggage, piling them up together and passing them around the room before collaging them into frames to decorate the funeral home. We laughed and pointed and flipped through the images. Por Por as a young, beautiful girl, modeling for a noodle factory in Chinatown; Por Por and Gung Gung, with two children, then three, then more, in the yard of their house; Por Por with her oldest child, Tommie, who drowned in a nearby lake one afternoon in 1949; Por Por with each of us grandkids when we were born, at our school plays, and for the older of us, at our graduations from high school and college. Por Por on my right arm, my mother on my left, as they walked me down the aisle at my wedding just seven months before she died, almost to the day.

© Todd Gieg

My grandma never got a chance to see the wedding pictures, and we had only corresponded in a few sparse emails over those months. That was much less often than usual; I was a newlywed, busy setting up a life, stupidly blind to the possibility of losing her. When I pulled the prints from the album to pack for her funeral, I remembered how content she had looked as she watched me dance and move around the room that night, and I remembered that she had been one of the last to leave. Long after the band had finished and packed up their instruments, after most of the guests and our families had gone home, she sat at a cocktail table, sipping coffee, resting one hand on her cane, smiling.

She died sitting up in a chair next to her bed on the first floor of my uncle’s house. She held a coffee cup in her hand. This was only fitting, since she drank coffee like water all day and night for most of her life. She went quietly, peacefully. A stroke, probably.

The day of her funeral was long and strenuous: a family breakfast, a private viewing at the funeral home, a public viewing, the church service, and, before dinner, a slow drive through the neat, oak-lined streets to the cemetery. As our procession made its short journey through the town that afternoon, the local police parked their squad cars to block off the narrow side streets—an almost comically formal gesture in a place where the few stores remained tightly shut on Sundays and we had not seen a single resident emerge from his or her house all day. There was no one waiting to cross at any intersection, and when our cars trailed into the muddy graveyard, two stray dogs darted between the headstones and scurried off.

“When Christ shall come, with shout of acclamation, And take me home, what joy shall fill my heart.”

More family had arrived at my grandma’s house, suit coats off, flip flops replacing heels. We moved through the living room, my mother in front, Brian behind me, my aunt and cousins and brother following. We wandered through the close and quiet space, 10 or 12 of us fanning out through the kitchen, the breakfast room, Por Por’s bedroom. I stepped alone into the back bedroom, where my grandfather had died in his sleep when I was an infant. For as long as I could remember, it had only been used for storage, piled high with ripped and spilling cardboard boxes that partially blocked the door. I had always assumed that was no coincidence.

I moved down the short, low-ceilinged hallway, snapping the chunky switch on the old light plate in the bathroom. Spiderwebs crisscrossed the bathtub, and a half roll of toilet paper dangled from its holder. Travel-sized bottles of shampoo and lotion huddled together on a shelf above the sink. I could hear my cousins laughing, teasing their mother about a childhood picture. An uncle stomped noisily up the attic stairs, and my mother called up to him from below.

In Por Por’s bedroom, a thick mystery novel lay open on the bed, the way someone who had put it down to answer the phone or check the oven would have left it. A jewelry box with tiny drawers rested on the dresser. In the hall, the wardrobe—”chiffarobe,” my grandma called it—where I had hung my small clothes for one whole summer, when I was six and my parents had sent me there from Los Angeles while they angrily hashed out the terms of their divorce, looked small and tired in its corner. I wandered into the kitchen. A covered tin cake plate sat on a counter. I pulled off the top, half expecting to find a freshly frosted cake underneath. It was empty.

The whole house was perfectly preserved, as if my grandmother had dashed out to the store decades earlier and just forgotten to return. Calendars and property tax statements from the 1960s, 1972, 1986 nestled together in the mail rack by the door. Dried prom corsages jutted out from a corkboard, where they had been pinned in the 1950s. Three soda can pull tabs jangled together in a Tupperware container on the kitchen table.

I moved into the dining room, where Tommie was laid out after he died, his small casket in the center where the dinner table now stood. I had grown up with a sense of him, always, because I could feel how much he was missed. But it never felt right calling him “uncle,” since he died too young to be anyone’s uncle at all. When I was about the same age he was when he drowned, I found a box of condolence cards and photographic negatives in the back of a closet. While the adults were distracted, I read the pat phrases and prayers inscribed in each card and held up each brittle image to the light. There he was, in his coffin. I couldn’t make out his face in the brown-toned reverse images, but I knew it well enough from the dozens of photos of him that lined the walls of my grandma’s house.

© Wing Family

Por Por and I had spent every evening in that dining room in the summer of 1977. After dinner each night, we built card houses on top of wobbly TV trays, one after another, until air from an electric fan blew them all down. As I thought back to the oppressive humidity and how many mosquito bites I’d gotten in those few weeks, my brother walked over and handed me a small plastic rectangle. He didn’t say anything before he turned and headed back into the kitchen and joined our uncle in front of the refrigerator. They began talking about the icebox on the back porch.

I looked down into my hand, hardly registering that it was the credit card sleeve from a wallet. I slid a thick stack of cards out of their see-through plastic casing, and a musty smell drifted up from my grandmother’s driver’s license, which had expired in 1993. I don’t know if she left it behind because she stopped driving, or if it expired and she got a new one, but she had never thrown it out. She was young in the picture, in her 60s maybe, with Chinese gold earrings dangling from her ears and a bright red blouse a couple of shades darker than her lipstick. Height: 5 ft. Weight: 120 lbs. Sex: F. Race: Y. The “Y” made me smile. Yellow. On another day it might have made me angry, but this was, after all, Mississippi, and this was, after all, what my grandmother was used to. She wouldn’t have minded, and she would have told me not to mind, either.

© Jen Shotz

Behind her license was her AARP card, expired in 1990; a piece of thick, white paper with her Medicare numbers carefully printed in her meticulous capital letters; a Revco Drugs discount card; the business cards of doctors and lawyers in California. She must have collected these when she came out to visit us for six weeks or six months at a time. She must have gone to their offices while I was at school, because she was always home in time to help me slip the heavy backpack off my shoulders as soon as I walked up the steps. On those afternoons, while my mother worked a couple of jobs and my father dragged her back to court in their ongoing custody battle, Por Por and I would just sit, holding hands and talking about our days.

Behind the business cards was a student ID from the Travel Advisors Training Academy. She had registered for a Travel Counselor course on January 6, 1976. I don’t know if she ever completed it.

That was right around the time Por Por first started spending more and more time away from Marks. My grandfather had been dead for five years. Wing’s Grocery was closed and the space rented out. First she traveled for one month, then three, then six at a stretch. She looped from our house in L.A. to my aunts’ and uncles’ in Jackson, Salt Lake City, Satellite Beach, Austin, and San Francisco, then around again. At first she would fly back to Marks several times a year, then once or twice, and finally, hardly at all.

© Wing Family

I think she always meant to return home, but it was easier to be where the littlest grandkids were, where she was needed for babysitting and at hockey and soccer games. Then she became a little weaker, a little less steady on her feet, and the line between what was good for the grandkids and what was good for her became blurred. Soon enough she was living with her family because someone needed to look out for her. But she kept her house just as she always had—spilling over with letters and cassette tapes, church picnic reminders and baby announcements tacked pell-mell to the walls, shoes under the bed, stationery tucked into desk drawers, jars of Chinese black beans in the pantry, and sugar cubes in the bowl.

Maybe having this house at the ready was her little rebellion, her gentle way of pushing back against the decline of her body and the loss of her independence. Maybe it made her feel safe, as it had once made me feel safe during a lonely summer while my former life reshaped itself on the West Coast. Maybe knowing that her old life—her real life—was waiting for her made her feel less afraid that she no longer had the capacity to live it, if she could only get back to it.

We all stood quietly in the living room for a moment, looking around at the LPs stacked by the fireplace, the sheet music open on the piano. I tried to memorize the location of every knick-knack, every trinket. We filed out through the narrow foyer and into our cars for the caravan back to a hotel near the Memphis airport. My mom and her siblings would return in the spring to clean out the house.

As we drove down Main Street and passed back through the dark town, I looked down and saw that I was still clutching the small packet of cards and photo IDs and assigned numerical codes that had once plotted the points of my grandmother’s life.

Stuck in Memphis, Mourning

The next morning, my mother, my brother, his wife, my husband and I went to Graceland. What else do you do when you’re stuck in Memphis, mourning? We figured it would have made Por Por laugh.

The climate-controlled quiet of the house was comforting. We moved around each other, wearing chunky black headphones and following the audio tour. Toward the end, we headed upstairs from the basement, past a bored teenage girl in a Graceland uniform who barely nodded in our direction. The stairway walls were lined with shaggy green carpet, and we ran our hands through the yarn as we climbed. I expected her to ask us to stop, but she didn’t.

Back on the ground floor, we leaned over the low wooden wall that separated us from the famous Jungle Room. My brother took a picture of the five of us in the mirror on the opposite wall. We stared at the stone fountain at the far end of the room, the oversized, carved wooden chair with furry, animal-striped upholstery that had been Lisa Marie’s favorite, and the monkey statues lining the perimeter.

I suddenly felt as if I might suffocate. I had not cried since we sat in the church the day before, but now, in this airtight, muffled chamber, my heart beat faster and my throat began to constrict. I could feel my skin again, and I was overwhelmed by an immense and surprising sorrow for the scared, enthusiastic boy from a small town in Mississippi who built his parents a fancy house and died before he could outgrow the outlandish taste of first money. That boy wanted something from the world, and all this stuff—the horses, the hi-fi systems and the private plane—couldn’t buy it for him. All I could think was that Elvis died alone and left this house for us to walk through and somewhere, he was in here, lost among all the things he had left behind.

When it was time to leave, my mother was already waiting on a bench outside. She looked tired, directionless, as she stood up to meet us. It was sunny but cool, and the air felt gentle on my face. We walked out to the side of the house, where Elvis, his parents, his aunt, and his twin brother, who died in childbirth, were buried together in the meditation garden. We lingered over the flat, full-length grave markers laid out like fingers on a hand and watched the eternal flame bob and flicker above Elvis’s head. I slipped a quarter into my mother’s palm to toss into the fountain. We paid $20 to buy the group photo we took in front of a mural of the Graceland gates, then we headed for the airport and flew home.

© Jen Shotz

In October 2014, almost 11 years after my grandma died, I returned to her house with my mom and aunt. We were in Mississippi for a Delta Chinese reunion, and we snuck away one afternoon, shooting up the arrow-straight highway to Marks.

So much had changed. One of my mother’s sisters and another of her brothers had died, far too young. I had two children. My brother had a son. Even my youngest cousins were out of college and getting married. And still the house stood, almost exactly as we had left it that night. My aunts and uncles had done their best to clean it out, but they hadn’t been able to get through it all before first one got sick, then another. There was little value to the property in this poor town, and the house itself was uninhabitable. They had gone back and forth about what to do with it, but now the process involved two generations of heirs, and attorneys, and many signatures. It took time.

We circled the building, which sagged in new places. Our shoes crunched into the grass. We couldn’t go inside this time—it wasn’t safe. Or at least, we didn’t know if it would be. We stepped around to the back. The smaller porch there, off the kitchen, splintered and warped in all directions.

What seemed like a thousand wasps floated in and out, hovering and cruising through holes in the screen. They clung to the ceiling. They swarmed around us. A low shelf ran along the back wall of the porch, under a covered window. I pointed to a stack of items so covered in dust they were unidentifiable.

“What’s all that?” I asked.

Without a word, my aunt stepped up onto the porch. She skipped lightly but carefully over a wood plank that covered the gap between aging stairs and aging floor. I followed her, not wanting her to be up there alone, in case the bottom gave out, but worried that our combined weight would make matters worse.

She handed a few things to me: a jade green vase, a tall white milk-glass vase with a narrow stem, a 1993 Mississippi license plate, and a set of three decorative plaster casts, two of fruit and one of a bird, all painted by the same amateur hand in blunt red and green. They were coated in a grimy layer and stained my hands with dirt.

I took them with me as we continued around to the far side of the house. One of the dining room windows had broken. Shards of glass hung down and spiked up from the rotted wooden frame. I could smell mold from inside. Through the hole, I saw a familiar tablecloth—white cotton with a border of cherries. It lay thrown over a chair backed up against the window. I wanted to reach through and grab it—it was so close—but the opening was too high and the glass too sharp. Wasps moved in and out of the house, as if it were theirs.

© Jen Shotz

The sun was starting to go down, and invisible critters were snapping at our ankles, making us itch and swat at them. We carried the filthy items to our rental car, where I rinsed them off with water from a bottle. I stashed them in the trunk with our suitcases. Later that night, I hosed them off on the lawn at our distant cousin’s house and packed them carefully, snugly, among my clothes.

I flew home before dawn the next morning, disappointed that I couldn’t go back into the house, to see and touch it one more time. The things we took from her porch are in my apartment in Brooklyn now, sitting idly, reflecting back to me, waiting.

This article was originally published on