Bracing For Impact

I scrunched my eyes tightly shut, holding onto the car door handle with all my might. I didn’t know exactly how this was going to play out, but I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that it wasn’t going to be pretty. In the space of three interminable seconds, my 41-plus years flashed before my eyes, and I wondered distantly how my loved ones would take the news of the crash.

Long moments passed during which I neither felt nor heard the sounds of metal colliding with more metal. Absently, I registered that it was odd that I didn’t even feel the shards of glass which surely blanketed me by now. My ears strained but didn’t pick up any agonized screaming over the sounds of my own hyperventilating. I interpreted all of this in the only possible logical way: The accident must have surely been so horrific that nobody else was conscious at this point. Clearly, I was in shock and had repressed the memory of impact already.

Sensing movement to my left, I realized I would need to open my eyes and raise my head to assess the damage and to aid in my own rescue. “The first responders sure got here quickly,” I thought to myself. Or maybe I had been unconscious for a period of time.

With every last drop of courage and with all of the energy I could muster, I tentatively opened one eyelid, and then the other, and my brain couldn’t immediately comprehend what it was seeing.

No blood, no broken bones, no mangled car, no broken glass. I was in the car with my little boy, as I had been thousands of times before over the past 15 years. But this time? This time, it was all wrong. My brain struggled to make sense of the scene.

My little boy, the same one I taught to ride a bike without training wheels what feels like just last week, was in the driver’s seat of my car. His hands at 10 and 2, his feet easily touching the gas and brake pedals, he looked over sheepishly at the shell-shocked woman in the passenger seat (me). “Sorry, I took that turn a little too fast, Mom. That was a close one,” he said with a wry smile as he steered my car into our driveway.

This man-child of mine turned off the ignition, and we sat companionably for a moment, the ticking of the cooling engine joining the sound of the neighbors’ lawnmower on one of the last days of summer.

Driving my car is both legal and socially acceptable for him now. And it is terrifying. Part of the terror stems from the fact that I’m giving up control in more ways than one. The bigger problem for me, however, is that it’s an inescapable reminder that he’s aging. As it turns out, that also means that I’m aging too.

Gone are the days of singing the alphabet song and watching countless Sesame Street specials on VHS; long gone are the days of having to convince him that he didn’t need to nap but just needed to close his eyes for five minutes (it always worked); gone longer still are the days of diapers and sleepless nights. Most of the time, I’m totally OK with that.

There are some pretty awesome things about having a teenaged child. For example, I’m the one waking him up on weekends now, not the other way around. Vacationing with a teenager is infinitely easier (and often more fun) than having a small child in tow. And it’s an indescribably neat feeling to have a real conversation with your own child and to realize that he knows things that you never learned.

A driver’s license is both a necessity when living in the suburbs as we do and a rite of passage for a teenager. It is a symbol of his coming adulthood and a badge of independence. And it makes this 41-year old mom feel very, very old.

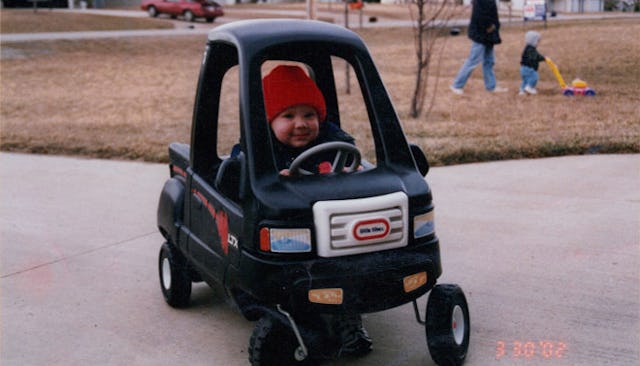

I would be lying if I said that there was not a part of me that pined for the days when my little guy tooled around the driveway in his toddler “truck” Flintstones-style, but I am torn because I also want him to enjoy this newest milestone and everything that comes with it.

I realize that there are going to be a lot of scary moments like this over the coming months and years. I know. It’s so hard to have been in control (more or less) over my child’s life for the past 15½ years and to now suddenly find him, quite literally, in the driver’s seat. It is beyond disconcerting.

On shaky legs, I somehow managed to get out of the car, catching sight of myself in the side mirror as I exited. Was it my imagination or were there more grays in my hair now than there had been 30 minutes before? No, there were definitely more.

So ended another mother-son driving lesson. The next time he asks to go for a practice drive, maybe he can drive me to the salon so I can cover this latest evidence of the passage of time. Or maybe I’ll just focus on being able to keep my eyes open and my breathing steady as he turns corners.

This article was originally published on