The Reality (And Aftermath) Of Having A Pedophile In Your Family

A few years ago, my brother was arrested. I was sitting at home not doing much of anything when I got the text. As a boy, he had been my big-blue-eyed, freckle-faced little buddy, perceptively correcting anyone who wrongly labeled his orange hair red.

It has to be drug possession, I remember thinking, connecting the dots of his recent behavior. Then Class C Felony lit up my screen. Shit, distribution?

But it wasn’t drugs. He was arrested on 12 counts of possession of child pornography. Felony possession, where the victims are clearly younger than 12. My daughter, my first born, had just turned one. I had a panic attack.

Prior to that day, I’d had no real reason to distrust him. He was everyone’s favorite guy, even though he was frequently unemployed and living in … unique settings. His substance abuse was a concern, but we all made excuses. He had ADHD; he was the baby in the family; he was just taking longer than most to get his act together.

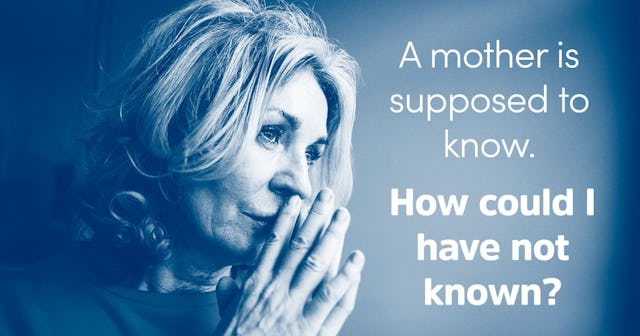

I couldn’t stop thinking, what if he hadn’t gotten caught? He would have hurt my baby girl. And it would have been my fault. A mother is supposed to know. How could I have not known? It gutted me.

Over the next few years, our family fell apart. It was impossible for us to understand how our middle-class family of otherwise high functioning, educated adults could be going through this. We wondered if he had been abused, but he insisted he had not. My parents couldn’t wrap their heads around this new reality. They trusted him when he blamed drugs no matter how often I—their daughter with a PhD in clinical psychology—insisted substances do not cause sexual attraction to little girls. They needed to cling to a belief that looking at pictures wasn’t as bad as hurting children. We couldn’t talk without arguing or shutting down.

My parents and other brother stayed in touch with him, while my sister-in-law, husband, and I refused to have anything to do with him. It was as if we were tugging on opposite ends of a rope, all trying desperately not to fall into the abyss he had created. Then my mom died (like died died, not figuratively died). She’d been living with a chronic lung disease for several years and her health tanked when my brother was arrested. It was all just too much; she couldn’t bear it.

As for me? I was terrified. If I could miss this about my own sibling, who else was I oblivious about? I binged on stats and facts, trying to regain a sense of certainty, of control. But learning that one in three girls and one in six boys will be sexually abused by the time they reach 18 does little to increase anything but anxiety and panic. The cozy mirage of this could never happen to me evaporated.

Sorajack/Getty

I learned predators groom parents to gain their trust before turning their attention to the child. When they groom the child, they often do so right under a parent’s nose to give the impression of innocence (like “I can’t possibly be doing something wrong if I’m doing it right in front of you!”). Child abusers aren’t strangers luring kids into white vans, they are known adults playing games kids like, giving kids things they value, working their way up from affection to things far more nefarious. How could I ever trust anyone again? How on earth was I going to keep my kids safe?

Then last summer, my husband and I took our kids on a vacation with six of my childhood best friends and their families—31 people in one house for an entire week. As soon as we arrived, a girlfriend pulled me aside to report the unsettling news that another friend’s adult stepson was there and had slept in the kids’ bunkroom with several of the little boys the night before.

I had met the stepson only once. He seemed like a nice enough guy even though he was newly sober, unemployed, and living at home. I had no real reason to distrust him. Still, something didn’t feel right about a 26-year-old man sleeping in a bunk bed with little kids.

My friend and I considered our options. We didn’t want to offend, or be perceived as unfairly accusatory. We settled on an excuse about not having enough space for another kid who would be arriving a couple days later. We were told sleeping in the bunk room with the kids wasn’t the stepson’s idea, that he had been put there because there were no other free beds. Ultimately, everyone agreed he’d sleep on the sofa. The bunkroom dilemma had been resolved, but my sense of unease remained.

A little later that morning, I found my daughter on the sofa. At six, she had remarkably good posture for a kid who’s not a ballerina. She was engrossed in her tablet, seemingly oblivious to her surroundings. I, however, was not oblivious to the fact that the stepson had taken up residence so close to her that their shoulders were touching. I was not oblivious to this grown adult inserting himself into her little-kid-game playing. Alarm bells were ringing.

“Honey, come with mummy so you can take a shower,” I said, trying to mask the suspicion in my counterfeit plea. I had no real reason to distrust him. Then he purred, “You smell good to me.” I felt sick. My mind started doing this mental ping pong—PING: one in three girls, PONG: I have no real reason to distrust him; PING: pedophiles groom victims by connecting over stuff they like, PONG: he’s probably just being nice; PING: trust your instincts, PONG: your instincts are probably off because of the brother thing.

laflor/Getty

I had no idea what was real and what was happening in my terrified imagination. Erring on the side of caution, I persuaded my daughter to go swimming just to get her away from the stepson. Two minutes later, he appeared next to her in the deep end. When I summoned her to the shallow end, the creep tailed her. PING: something is not right! PONG: you’re just being paranoid; PING: he’s showing way too much interest in a six-year-old. PONG: get your act together, you anxious freak.

After my brother, I swore I’d never let a predator near my kids. But how do you keep that promise if you don’t know who the predators are? What was I supposed to say? And to whom? “Hey friend, your step-son is being too nice to my daughter?” “Stepsons’s father, I have no proof whatsoever, and I’m probably not credible given the shock of discovering my brother is a pedophile, but I have this really twisted idea that your son might be one too?” Doing anything of the sort would have blown up our vacation, and most likely our lifelong friendships. I had no proof. I felt paralyzed.

I decided to run my observations past a few of the other moms in the house—a check to see if I was overreacting. What I got instead was a report that the stepson had been overheard declining to move out of the kids’ bunkroom the previous night when offered an unoccupied queen bed, and that he’d been seen making a pinky promise with my little girl. I wouldn’t learn until later that he was attempting to lure my six-year-old into online gaming that he said would be “our little secret.”

This is when I should have spoken up. But while I sat in indecision, one of the husbands took it upon himself to warn the stepson’s father that I had been speculating about his kid’s inappropriate behavior around my daughter. This was all it took for the father to pack up his family in a fit of rage, scream at me for “gossiping to all my friends about his son being a pedophile,” and storm out on our reunion. The truth is, my self-doubt and fear of hurting people’s feelings and ruining everyone’s vacation prevented me from using the word pedophile. From doing anything. Looking back, I had many reasons to distrust the stepson, but I was a coward. I would like to think that eventually I would have been brave and spoken up, but I can’t be 100% certain.

What I’ve learned since that trip is that perpetrators count on parents being afraid of exactly what I was: we will be so worried about hurting feelings, offending people, or being seen as wrongfully accusing someone, that we will ignore our instincts and shy away from difficult conversations. That we will be unwilling to risk the fallout. That we will hide under the illusion of it could never happen to me. Only one in three says otherwise.

I still don’t know whether I was right about the stepson, and I probably never will. But what I do know is this: next time I will act. I will have the difficult conversation, take on the rage and condemnation, the lost friendship and the fall out, if it means sparing my child the agony of the alternative.

This article was originally published on