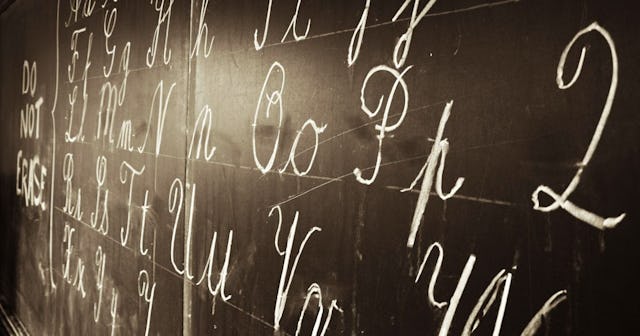

We Can't Let Cursive Writing Die

I write in a scratchy, wild script that’s a mix between print and cursive. My only goal whenever I have to physically write is speed, so I choose the path of least resistance, alternating between the two forms with whatever I feel gets the word on the page quickest. If a hand-writing analyst were to look at a sample from me, they would conclude I am indecisive, or possibly ingesting illicit substances.

This wouldn’t matter if all I were writing were grocery shopping lists. But I’m a violin teacher. My teaching method requires that the student bring with them a notebook to each lesson in which I scribble critiques and assignments for the coming week. My students need to be able to read my writing.

If we carry on with current trends, though, I’m going to have to force myself to stop using cursive at all because my students won’t be able to read it. More and more, schools are opting to dramatically reduce or altogether drop cursive instruction. With technology becoming more ubiquitous by the day, cursive is seen as an archaic skill, unnecessary to learn. The time that would be spent teaching kids cursive, a skill they presumably won’t ever use, would be better spent teaching them science or coding or math.

I disagree with this, and not because I’d like to keep chicken-scratching in cursive for my students. Kids need to learn cursive, not necessarily to write proficiently, but so they can read it. According to NPR, one of the primary reasons kids should learn cursive is so they can decipher cards from Grandma. Some teens said they kept up their cursive-reading skills to “look cool,” which I guess is similar to how my friends and I used to pass notes in school using the Greek alphabet as our “secret code.”

But the more important reason kids need to be able to read cursive is that so many original historical documents are written in cursive. Even if you think you’ll never need to decipher a historical document, there is a very good chance that someday you will.

I used to think learning cursive was unnecessary, but then a few years ago I started digging into my family history using Ancestry.com. That was an incredibly fun project that allowed me to discover loads of wild stories about generations past—but so many of the documents I needed to read were in cursive, especially the census worksheets because less than a century ago (a mere three or four generations), census data was collected door to door, by hand.

I stumbled across a document—a census report—that had been misread by a computer or human and filed in the wrong place. According to the last name, it should have been filed under “Y” but the letter looked like a “G” because the top of the “Y” was closed. As a result, the document had been misfiled. It turned out that I had discovered the missing link that connected my great-great-great-grandfather’s family to more distant relatives that I wasn’t sure were indeed mine. But since I could read the cursive, I was able to see all the family members from the census taken ten years prior, minus my great-great-great-grandfather who had been killed. It was clear that after her husband had been killed, my great-great-great-grandmother had moved herself and her three children in with relatives.

Not everyone is going to go down the family tree rabbit hole like I did, but even trips to the museum can be greatly enhanced by being able to read cursive. Legal documents from centuries ago are all written almost exclusively by hand, in cursive. I can’t imagine not being able to read, for example, the names of the founding fathers as signed on the Declaration of Independence.

Fortunately, many states agree. Joining 23 other states, Illinois recently mandated that cursive must be taught in schools. I live in Florida where cursive is still taught in schools, and my kids both picked it up in second grade. At my kids’ school, learning cursive was as simple as the teacher building in the loopy letters to her regular instruction. For the kids, it was like writing in code. They already knew what letters they wanted, they just had to make the connection between the print and cursive and follow the chart that showed how to write the letter in cursive. It was low-pressure instruction that the kids thought was fun, like a game. And both of my kids (eighth and fourth grades now) still enjoy writing the occasional note in cursive.

Virginia Berninger, professor of psychology at the University of Washington, also agrees kids should learn cursive. She studied early development of language by hand to see how the different types of communication engaged children’s brains. She believes handwriting, and cursive in particular, are still necessary to educational development.

Using brain imaging, her research showed that printing, cursive, and typing each create their own distinct brain patterns. And she found that using the written word enabled kids to compose more than if they used a keyboard.

Other research indicates that learning cursive may assist with the development of fine motor skills and may even be used as part of a treatment for dyslexia and other conditions related to motor-control.

Others make the point that writing in cursive is “more personal,” but on this point I disagree. “Old-fashioned” doesn’t necessarily equate to “more personal.” I’m well-versed in print, cursive, and digital text, and the receipt of a message is all the same to me regardless of format. I am for sure opposed to killing trees just to send a “personal” note. For me, the point of knowing cursive is being able to read it.

Cursive writing is a huge part of our very recent history, and many people still use it. Any kid who doesn’t at least know how to read it is bound to run into a situation where they’re faced with wanting to read a text and not being able to, simply because it’s in cursive. So, at least until our phones can scan and interpret cursive, we all need to be able to read it.

This article was originally published on