What Ikea And Education System Have In Common

If you are anything like me, you probably have a love/hate relationship with Ikea. I love walking through their store, putting our kids in child care, and seeing all the possibilities (and cheap prices) of their furniture.

Even though their carts turn like they have a mind of their own, I still keep coming back again and again with my wife to get things for our house (and especially for our four kids’ rooms).

Last week, we headed to Ikea because my youngest was turning 2 years old, and she was asking for a “big girl” bed of her own.

Sure enough, Ikea had what we wanted and we picked it out and loaded the four huge boxes into our car. The entire way home, my thoughts were on how long this would take to put together. It was Saturday, and there was college football to watch, stuff to do around the house, and a party to get ready for the very next day.

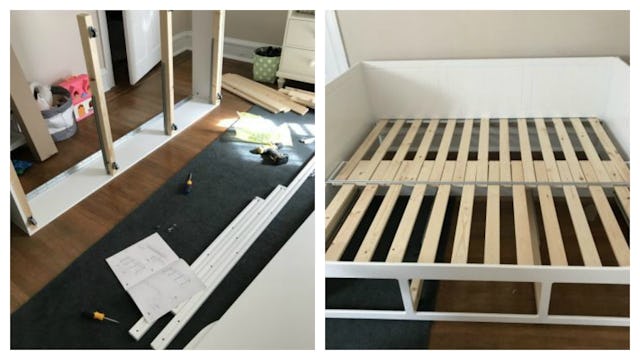

I got myself all set up for some work time and unloaded all four boxes into her room. The parts were everywhere, but Ikea did a great job organizing them, color-coding them, and giving me a clear set of directions on how to build the bed.

A.J. Juliani

A.J. Juliani

A few hours later, my task was complete! I followed the steps, took my time, and — voila! — we had a big-girl bed ready.

While I was putting the Ikea bed together and following the steps, I couldn’t help but think that this is what many of our students must feel like.

They are often given “big tasks” to complete in school. These tasks could be writing a paper, research essay, book report project, word problem, or lab.

In each case, the task must seem like it is going to take forever for the learner to complete. But then, we break it down step-by-step. We give students the exact directions and models on how to finish the work. We outline a rubric and project guidelines that keep the student working at a good pace and urge them to take it step-by-step until it is completed the “right” way.

While this might seem like a good thing, I’d argue it is one of the biggest issues we have in our education system right now. It’s hard to foster creativity and innovation when kids are always asked to follow the rules and complete the steps.

Here are four big takeaways I had from the Ikea experience and what our education system has in common:

1. Ikea is easy. But I didn’t learn anything.

Ikea makes it easy to build a bed, table, chair, or anything else you might need in your house. I’ve personally built an entertainment unit, dresser with eight drawers, coffee table, two beds, desk, couch, and two chairs from Ikea.

Yet I didn’t learn anything. I can’t even call it “building” because it was more like following the steps of a Lego set than learning how to create anything.

How many times do our kids finish and create something in school but not learn anything because they are following prescribed steps and guidelines?

2. Ikea is about compliance. Satisfaction is only in getting it done/finishing.

The only thing I got from the process is that I really better pay attention to the directions or along the way I’ll mess up the product and have to go back and start all over again. If I was not compliant, I would be getting penalized because there was only one right way to build this bed.

After the bed was complete, I’ll admit, I did feel a sense of satisfaction. However, it was in having a finished product that was good enough for my daughter to use. The more I thought about it, the more I realized the process had duped me into thinking I was making, but really I was just following. My self-worth was tied into how well I could follow directions, not how well I could make something.

3. Ikea is convenient. It’s not creative.

You know what was great about this process from Ikea? It didn’t take too much time. It was extremely convenient to drive to the store, pick out which item we wanted, slide it into the back of the car, bring it up to my daughter’s room, and have it finished in an hour or two.

It was extremely convenient.

But it wasn’t creative. I remember giving students in my classroom a project where they had to design a website for one of the books we were reading. The only problem was I gave them the exact website builder to use. I told them which template to choose. I showed them an example that had the website laid out in a very specific way. I gave them a rubric which specified what content should be where on the website. I actually had points for how many pictures, video, and media items should be on the website. I shared three options for color palettes.

When my students turned in these websites, they all looked the same. Sure, they had made a website. But there wasn’t anything creative about it. It was a convenient way for them to share information in a “cool” way. But they didn’t learn much along the way.

4. Ikea is standardized. It is prime for hacking.

That night as I was talking to my wife about Ikea, I was searching online and found an entire website dedicated to hacking Ikea products. It turns out that people have actually been building and modifying Ikea products for a long time, but it has been an offshoot community of hackers:

IkeaHackers.net is a site about modifications on and repurposing of Ikea products. Hacks, as we call it here, may be as simple as adding an embellishment; some others may require power tools and lots of ingenuity.

It was in May 2006 that I did a search on Ikea hacks and saw that there were so many amazing ideas floating around the internet. How great it would be if I could find them all in one place, I thought.

Three seconds later…

A light bulb exploded in my brain, and the rest, as they say, rolled out like Swedish meatballs. It took me a few nights of sleepless HTML-ing but I’m happy I did.

When something is as standardized and centralized as Ikea, it is prime for hacking. People come up with creative ideas on their own.

A standardized environment always has a group trying to break free of the constraints and make something better and powerful, whether it be Ikea or education.

This article is meant to be a reflection on what I saw in my own classroom, and what I see as something we all struggle with, in education. I had to ask the question:

Via John Spencer in our book, Empower

We want students to be successful, so we scaffold and build up support systems for them to find success. But where is the line? How can we support student success, celebrate them making mistakes along the way, and make time for them to learn during the process of creating instead of just following a process to create?

This article was originally published on