My Son Hits Like A Girl—And That's A Good Thing

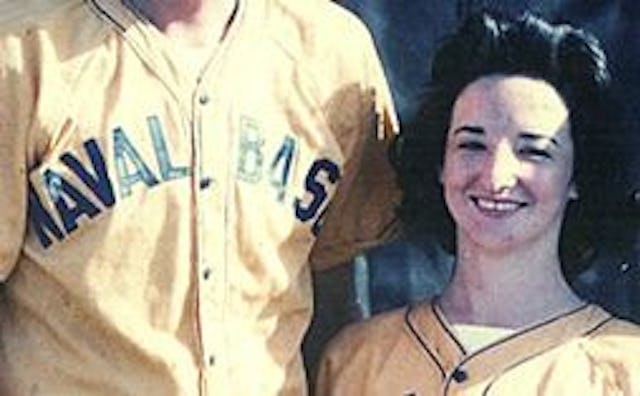

My mother was an athlete. She played baseball so well that she was scouted by a major league team, who thought the Jo Young they kept hearing about was a Joseph, not a Joan. The scout told her coach it was a damn shame she wasn’t a boy, because he would have recruited the multitalented girl. She was a shortstop phenom, who could hit a home run from a crouched position and play catcher like she was Johnny Bench.

She was a dancer, too. She was graceful, and coordinated, and could pick up and repeat complex choreography like it was just banging a drum.

She outran, out-played and even out-boxed every boy in her Army Base-adjacent neighborhood. Maybe more than all that, she was the special kind of all-around athlete, who knows how to get the best out of the people around her. She coached misfits to victory on a regular basis, with a blend of practice, patience and intelligence.

And then she had me.

Bless her heart.

I tried to come into this world sideways, and that’s probably how I’ll go out of it because I am the least coordinated, least athletic, least physically intelligent person in my family. After a lifetime of victorious athleticism, my mother turned nurse to tend the broken bones and sprains, the pulled muscles, the scrapes, cuts, bruises, head wounds and concussions that I brought home from my everyday interactions with the world.

My mother once told me she’d been afraid she wouldn’t know what to do with a girl. As rough and tumble as she had been, she was afraid she couldn’t help a girl find her value. What would she do if she had a child who loved baby dolls and pink?

Exactly what she did, I guess, because every inch of my soul was born to “girl”—if girl can be a verb, I did it. I girled so hard! Pink, sparkles, lace, fluff, dolls, glass slippers, pageants and plays were my world. If it didn’t already have some glitter on it, I could fix that. I would happily have put lipstick on a pig. Or a dog. My poor dog.

My mother might not have known what to do with all that, but it never showed. She delighted in me and valued what I found important. But she didn’t just watch, she coached. She was the consummate coach, finding what I was good at and bringing that forward, while working to build the muscles I Iacked.

She gave up on my sports muscles by the time I was 13. At the time of my retirement from junior high softball, my most spectacular play had been accidentally catching a pop fly, then sitting down on third base to block a runner because I couldn’t remember what else I was supposed to do with the ball.

In spite of my athletic inabilities, in spite of never being able to do the things she had loved, she never gave up on coaching me as her daughter. It wasn’t until I had my own baby that I started to understand the mental fortitude that it takes, the practice, patience and intelligence it takes to coach a child into her best self.

My mother had no idea what to do with her glorious creature, so she studied me. She found the places where I could excel. There were college-level literary courses, special trips to the museums and theatre, charm schools and talent agents, and voice lessons and fashion shows. And, at my insistence, there were the failed ice skating lessons, tennis lessons, dance lessons and gymnastics. As I fell, tripped and concussed myself out of each of those, she was there to drive me to the emergency room and gently direct me toward my natural talents.

She valued what I loved because she found me valuable. She was interested in what I did because she found me interesting.

She helped me cultivate my own style with endless applause, and she regarded my athletic failures with so much love that even though I never got to enjoy the thrill of victory, I have never been afraid of, or embarrassed by, defeat. Her passion for my well-being means that I can enjoy a loss as much as anyone has ever loved winning. She taught me that losing the game isn’t failure. Failure is being afraid to play.

I had a boy. I have a boy. And my boy is more coordinated, more naturally talented physically, more aware of his body and space than his father and me put together. I know books and writing, acting and fashion, music and lip gloss, and while all those things have their places in the world, outside the inherent drama of sports, they have no play on the greens, or the pitches, or the fields of dreams. Sure, David Beckham wears guyliner, but not while he’s kicking balls around.

What I learned from my mother, my coach, is that being a good mother is about finding what comes naturally to your child and stretching, strengthening and refining those muscles. It’s about becoming a student of your child’s nature and nurturing the best in him, to coach that maximum potential out of him.

It is about practice, patience and intelligence. Your practice. Your patience. Your intelligence.

My son and I are incredibly fortunate that when it comes to cultivating his natural prowess at sports, he has my mom. When he started playing coach-pitch baseball two years ago, my mother took over his at-home development. After a week with her, he went back to his batting practice. His coaches did that thing you only ever see in the movies.

Hats came off.

Eyes went wide.

Heads started bobbing.

“Son?” his coach called to him. “Son, who taught you that? Your dad?”

My boy broke into a grin. “My grandma taught me!”

My son hits like a girl. Like a 73-year-old girl.

His coach asked for an introduction.

Sixty years later, coaches are still mistaking my mother’s amazing abilities for a man’s. But I’m here to tell you that there is no athlete, no coach alive like my mighty Jo Young, whose patience, practice and intelligence are proof that a good mother can cultivate an artist as easily as an athlete.

This article was originally published on