Of Everything The Pandemic Has Taken Away, I Miss Touch The Most

I idled in the driver’s seat when the masked man strode past my door and knocked on the trunk. I pushed the release button and watched him toss the plastic bag in, slam the trunk shut, and run off without a word. It was quick and dreamlike. Driving home from Target I asked aloud, “Is this real life?”

I felt like a character in the first act of a horror movie; no fateful circumstance had befallen me, but in mere days an eeriness had settled over my interactions with the “outside” world. For two months now, it has felt as though something sinister has been percolating beneath the surface of normal family life, while an unease and a sense of incompleteness has permeated my thoughts.

At first, I thought the outside world felt surreal because I see so few faces now. True, I am not Will Smith, sole survivor of New York City in I Am Legend. There are people around — or signs of them, anyway. Cardboard boxes of provisions appear on our porch, delivered by drivers we never see. An errant soccer ball lies on the back lawn, our eight-year-old neighbor now afraid to hop over and retrieve it. Strangers fetch our dinner from restaurants after unseen faces take our order, prepare our food and box our meal. One night I studied giant Sharpie letters on a receipt – ALLISON – and tried to discern if the writer was male or female, young or old. Was I that bored? Maybe. Was I that desperate to connect with someone on the outside? Probably.

Still mulling over my unease after my Target run, I entered the house to the sounds of screaming. In the family room, my two boys were arguing over who broke the green light saber. The voices and volume felt familiar, almost comforting. Maybe I just hated how quiet it was out there. Our home feels more chaotic since the pandemic, yes, but it is not at all quieter. Our house remains a loud space where my husband and I still find little time to speak privately while social distancing with two young boys. Outside the home, though, I have lost simple daily conversation: chatting with the barista, the parents at drum class, the moms at school. I miss the little moments that recharge an extroverted stay-at-home-mom and bind me to my community.

What is worse, my few live encounters with others have ceased to be energizing, discolored now by risk and implication. A partition separates me from the cashier at the local market. On walks, neighbors cross the street when we approach. The one time I ventured out to buy dinner, I waited outside the cafe until a lone customer completed his transaction inside. Just three months ago, my boys and I had discussed how lucky we are to live in such a safe area. Now everyone is a conceivable threat, even me.

Online interactions are only slightly more satisfying. On Google classroom, my six-year-old speaks to friends reduced to glitchy one-inch squares. I watch my frustrated eight-year-old manage brief conversations amid the din of twenty housebound second graders speaking at once. Zoom dinners are nice, but the “meeting” invitations we send each other underscore the app’s intended purpose. During a Zoom game night, a friend left to use the restroom, and I found myself staring sadly at her empty chair. It made me miss her in-person visits more.

While meet-ups allow me to see and hear loved ones, they do little to shake off the disquiet I have carried since March, the strange sense that I am not living my real life.

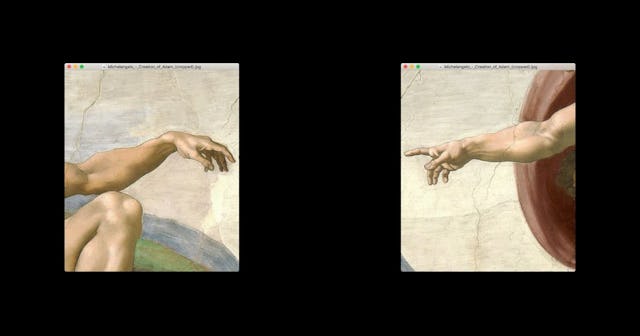

Then one evening the true source of my anxiety became clear when I participated in a Zoom gathering with some former students from the high school where I taught for fifteen years. As we all adjourned for the night, one “boy” (he is now thirty-two) pressed a palm to his computer screen as a way of saying goodbye. That is when it hit me. I and the people I am closest to are tactile. We hug hello. We hug goodbye. We hold each other’s hands when we are upset. We rub each other’s backs when we are scared. We pat each other’s shoulders when we are excited. Even in the classroom I had communicated often through touch. The handshakes as each student entered my classroom on day one. The slap on the back when a student cracked a tough passage. The high five when a student aced his final. The hugs on graduation.

We know that touch is the first sense a baby develops in the womb. We know, too, that a caring touch can stimulate growth in children and alleviate a variety of physical and emotional difficulties in adults. While I know that needs and comfort zones differ from person to person, I also know that more than faces, more than voices, I miss touching. I want to hug my mom to validate the ache I know she feels for her absent children and grandchildren who until March had been the happy recipients of frequent drop-in visits. I want to shake the hands of our principal and teachers to thank them for their Herculean efforts these past weeks. I want to hold my dad’s hand in communion as he serenely reminds me that nothing lasts forever. I want to watch my boys grab their cousin Ashley’s hand and run with her to the lawn, to watch them curl up with my husband’s mother while she reads Dragons Love Tacos.

There has been much talk about “when this is over.” Will we feel safe traveling “when this is over”? Will we feel safe sending our children to school “when this is over”? How will we even know “when this is over?” On the issues of travel and schools, I honestly do not know when I will feel secure. Much of my outlook will depend on what health experts advise. I do know, though, that my own unease, my own feeling of incompleteness, will be over when I no longer rely on touch screens and touchpads and can instead offer and receive an unfettered, utterly human touch.

This article was originally published on