Another Barrier To Opening Schools? Finding Enough Teachers

If you have kids in school, there’s a good chance that, at some point, you’ve witnessed the trouble to find a sub. Your kid comes home reporting that their class got combined with another today, or that the principal or school secretary sat in.

Because that’s the state of public education in the U.S.—even before we were all ravaged by a pandemic. Even before COVID hit, many school districts could not afford to wait for licensed teachers to sub. They needed an adult—any adult really—to just keep the kids safe and focused on something somewhat educational, even if it was worksheets all day long.

So yeah. Things were already dire for schools nationwide in the sub department. Then COVID hit. And it changed everything.

Because of COVID-19, if a class doesn’t have a sub, it can’t be combined with another because kids need to social distance. And because of COVID, if a teacher has been exposed, even if they are showing no symptoms, they have to quarantine for 10-14 days. And because of COVID, kids are eating lunch in the classroom and having to be monitored closely at recess, which means teachers and the subs standing in for them are not getting the mental and physical breaks they need to prep, plan, or simply take a breather from the stress that is pandemic teaching.

COVID-19 means teacher shortages. It also means sub shortages. And it means districts already struggling with massive budget shortfalls are hit even harder—districts that are typically categorized as “disadvantaged” or “low income.” Districts full of kids who do not receive nearly the same education as affluent kids in other cities do, and who have, therefore, felt the impact of COVID-19 the most.

We all know why schools struggle to find subs. The job can really suck. Even if you’ve never subbed, you were, at one point, in school. Remember how kids treated subs? The minute you walked in and saw someone other than your regular teacher, someone who maybe didn’t know all the rules, the wheels started turning in your head. This meant more opportunity for note-passing and bathroom breaks. You knew right away that the kids who occasionally acted up were really going to be on fire today. And by 3:00, that substitute was usually exhausted beyond measure, all for a measly hundred bucks.

Now, during a pandemic, add on the pressure to keep kids masked, to keep yourself masked, to keep them six feet apart, to maintain all the COVID-19 protocol, and not stress the entire day that you might be contracting the disease yourself. Also, oftentimes subs are retired teachers still looking for extra income. Yes, they have the advantage of knowing the ins and outs of teaching, but they are of the at-risk age for COVID, and simply can’t take that chance. Or, other regular subs have at-risk family members at home that they must protect, meaning they’ve taken their names off the sub list at a time when subs are needed the most.

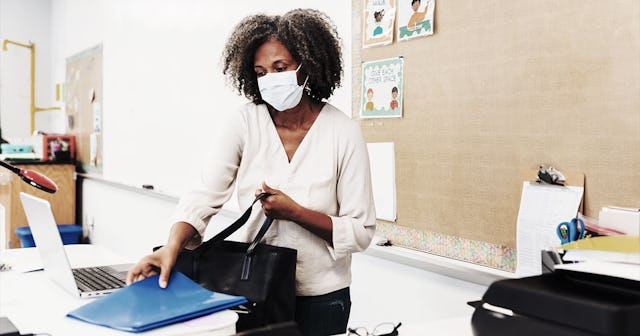

Johnce/Getty

And finally—as seen in districts like Franklin Public Schools, a suburb of Milwaukee, for example—subs and teachers are quitting because schools aren’t doing what they need to do to protect their staff. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reports that many regular subs have now opted out saying that “classes are too large to maintain social distancing,” and “the district has not improved ventilation and filtration to prevent the spread of COVID-19.” But the thing is, many districts didn’t have the funding they needed to adequately provide for their staff and students before the pandemic. Now they are expected to come up with money for better ventilation and filtration—and come up with it quickly—and it’s just not there.

So no, it’s not hard to figure out why school districts nationwide are drastically short on subs, especially now. Why many of us might hear that the principal taught our kid’s class one day. Or the teacher taught via computer, from home, while a parent or office staff member simply sat in the classroom to ensure the kids stayed safe.

Would you go into a school right now and offer to sub? With hundreds of kids—any of whom could be carrying COVID and don’t know it, many of whom struggle to stay masked and forget to wash their hands—for $10-15 bucks an hour?

I sure wouldn’t.

The reality is, schools are operating under a severe sub shortage and are barely getting through the week, holding on to whatever teachers are still there—sucking every last ounce of energy they have and putting extra responsibilities and tasks on their already very full plate.

“Large districts such as Denver Public Schools are working with a quarter of their usual substitute pool,” The Atlantic reports. “Districts are responding by grabbing every warm body available, but educational quality suffers under an endless parade of increasingly unqualified substitutes, continual toggling between in-person and virtual instruction, and art and music teachers pressed into service as classroom teachers.”

This isn’t education. This isn’t sustainable school. And yet, our government has forced schools to be open, despite doing nothing to stop the spread of COVID-19 and despite offering no respite or resources to school districts—like an increase in pay for subs maybe? Or the funding they need to improve ventilation and filtration? Or a rush to get teachers fully vaccinated (both doses)? No, because that would be called “prioritizing American public school education,” which this disastrous outgoing administration definitely has not done.

Schools all over the country that reopened last fall, despite the end of the pandemic being nowhere in sight, saw pretty quickly how hard it was going to be to fully staff their schools.

The Atlantic asserts that the debate about whether schools are safe or not isn’t a relevant argument anymore. Now, it’s about teacher and staff shortages. “‘It is especially difficult, and impossible on some days, to have enough licensed teachers in classrooms delivering quality instruction,” says Jeannine Nota-Masse, the superintendent of Rhode Island’s second-largest school district. “Now you have students in the building and not enough adults to cover for the adults that are home for various reasons.'”

And that Rhode Island school district’s struggles are not unique. “One elementary school near Milwaukee lacked 10 teachers on a recent day,” The Atlantic reports. “Metro Nashville Public Schools has had more than 200 teachers or staff members in quarantine or self-isolation each week since the end of October.”

Schools everywhere are struggling to staff their buildings. Teachers, administrators, custodians, lunch room staff, school nurses, guidance counselors, librarians… there are shortages in every department. But certain demographics are being hit harder than others, and you can probably guess which ones.

Sadly, and not surprisingly, our nation’s disadvantaged schools are being hit hardest by the teacher and sub shortage that COVID-19 has only exacerbated. These are districts that were already struggling to provide enough books and enough desks for kids. These are districts where kids come to school hungry. Who live a home life many of their teachers cannot imagine. Kids who need that loving teacher to see them every day, look in the eye, tell them they matter and belong in school. Kids who need school-funded meals and school-funded technology, because they have none at home.

In a study about substitute teachers published by Brookings, the numbers prove how COVID-19 has widened the achievement gap in America, and substitute teacher availability plays a big part of that.

“Disadvantaged schools exhibited systematically lower substitute coverage rates,” the article says. “Teachers in higher-needs schools are much more likely to expect non-covered absences than their peers in other schools. For example, nearly half of teachers in schools with the highest share of Black and Hispanic students reported that their schools are not able or probably not able to find a substitute teacher when they are absent, while only 9% of teachers in schools with the lowest shares of Black and Hispanic students expressed such concern.”

Again, it is obvious which kids are getting left behind in our country’s public school system. And it’s not affluent white kids.

Schools will always need subs because teachers are human. They get sick, their own children get sick, they have doctor and dentist appointments, and, frankly, teaching is hard AF and they deserve to take a mental health day (or two) whenever they need it. Even post-COVID, this will continue to be a struggle, especially for disadvantaged school districts across America.

That’s why we are counting on this new administration (an administration that proudly values teachers) to consider substitute teacher staffing needs in their education reform, especially after this year that negatively impacted so many low income schools—schools who were already barely scraping by.

That reform should, first of all, include an increase in substitute pay. Full stop. Secondly, subs need better training (training for which they are paid!) and better resources to deal with disciplinary issues and other teaching-related challenges. Schools as a whole need to implement initiatives that curb poor behavior and reward kids when they are helpful and respectful to subs. Also, subs need better classroom management tools. Teachers learn how to manage a classroom of 20-30 kids through their education and training. Then, a sub comes in and we send them into a hyper classroom full of kids with none of those necessary skills. It’s absurd and unfair to expect them to manage a classroom for a full day without proper training.

Substitutes may not have to manage long-term lesson plans or IEPs or gradebooks, but they may have to face an active shooter situation. They may have to handle a sick child, or a major disciplinary issue, or know what to do if they suspect abuse or neglect. And, this past year, they’ve had to handle COVID-19 risks and protocols.

They are necessary and valuable and in dire need, especially in disadvantaged districts who already face more challenges than those with proper funding and resources. It’s time we make some necessary changes and show them just how valuable they truly are.

This article was originally published on