Students Struggle To Understand Why Their Classmate’s Father Was Shot By Police

Teacher Rebecca Lee shared the reaction of Crutcher’s daughter’s classmates to his shooting

On Wednesday, a teacher at the school that Terence Crutcher’s daughter attends was part of three small group discussions with fifth-through-eighth graders about the killing of their classmate’s father.

Rebecca Lee posted some of the things she heard from her students on Facebook, in the hopes that “…if you can put yourself in the shoes of a child of color in Tulsa right now, you will have a clearer understanding of the crisis we’re facing and why we say black lives matter.”

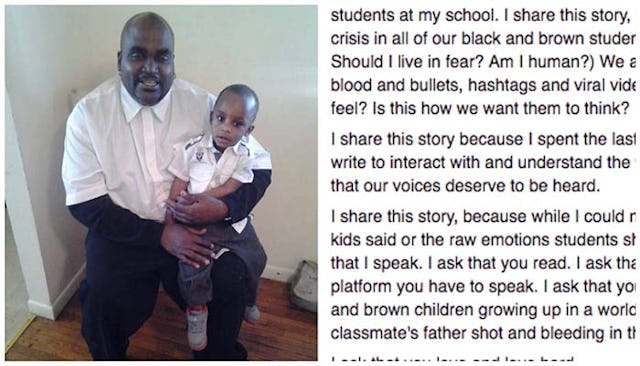

Terence Crutcher was a 40-year-old black man who shot and killed by a Tulsa police officer last week. He was unarmed, and had his hands in the air. The policewoman involved, Betty Shelby, was charged with first-degree felony manslaughter today. One of the four children Crutcher left behind is a daughter who goes to Kipp Tulsa College Prep, where Lee is a teacher. According to Lee, “…our staff decided we needed to press pause and create a space for kids to share their thoughts and feelings in response to the killing of Mr. Crutcher.”

Lee facilitated three small group discussions: one with fifth graders, one with sixth graders, and one with a mix of seventh and eighth graders. She then wrote about the different reactions to the shooting each age group had, and what they had to say will break your heart.

The fifth-graders, for the most part, cried and asked questions like, “Why were they afraid of him,” and “What will [his daughter] do at father-daughter dances?” The sixth-graders — the classmates of Crutcher’s daughter — were mostly silent, upset, and in shock. Lee (who is white) told them,”‘We have different skin colors. I love you. You matter. You are worthy. You are human. You are valuable.’ Shoulders shake harder around the circle. I realize that this is the first time all year I have affirmed my love for them.”

The fact that this teacher felt it was important to remind these kids that they are worthy and valuable should devastate all of us. The fact that that needed to be said gives those of us who don’t already live in these kids’ shoes a window into what this country tells them every time an unarmed black person dies at the hands of the police and no one is punished for it. It tells them that they are expendable.

Lee’s final group was the seventh and eighth graders. Their reaction to the story was different. “These students are older– thirteen and fourteen. They are hardened. They are angry. Some students refuse to hold or look at the article. The speak matter-of-factly. One says she feels like punching someone in the nose.” Lee takes note of the boys in the group: “I look at the boys in my circle, all former students of mine. They have grown inches since their first day in my class. Their voices have deepened. Their shoulders broadened.” These boys are no different from other young black men and black children who’ve been killed by the police, like Tamir Rice, David Joseph, Paul O’Neal, and so on and so on and so on. Who can say that one of them isn’t next? No one. It’s no wonder they’re angry, shut down, and, as Lee put it, “hardened.”

In Lee’s description of the reactions of these three age groups, you can see the progression of what’s it’s like to grow up as a black child in the United States. What starts out as bewildered innocence, (“Why did no one help him after he was shot?”) ends in an understanding that what made him a “big bad dude” was, in the words of one of the older students, “the color of his skin.”

Lee wrote that she was sharing this story because “…my privilege requires that I speak,” and she asked that any of her similarly-privileged readers understand that privilege also demands action: “I ask that you use whatever privilege or platform you have to speak. I ask that you put yourself in the shoes of black and brown children growing up in a world where they see videos of their classmate’s father shot and bleeding in the street. I ask that you love and love hard.”