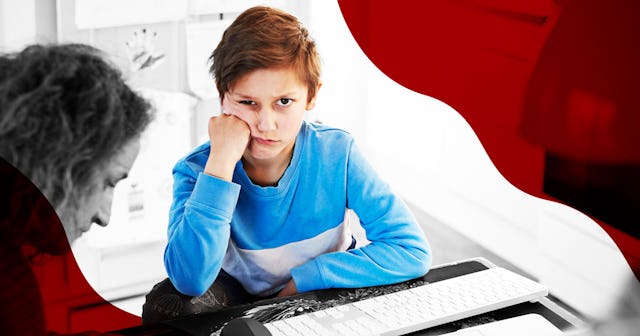

When Home Is The Classroom, It Can Be Hard AF For Kids To Regulate Their Emotions

Since the day he first entered kindergarten, my son behaved at school like a perfect gentleman. He is polite, well-mannered, and—if not totally docile—reliably cooperative.

His teachers never would have guessed that this same gentleman, upon arriving home, is consistently cranky and often rude, that he sometimes lies on the floor kicking and screaming like a toddler.

And that’s fine. The way I see it, he expends all his effort working so hard to be civilized all day, because he knows what is expected in public. Then, in the privacy of his home, the veneer of civilization is dropped and he can be a needy, vulnerable baby again. I take it as a sign of trust that, in the presence of his parents, my son can be his uncouth, unvarnished, uncivilized self.

We grownups do the same thing: the way we behave in public has certain aspects of a performance. In private, we let down our hair and loosen our clothes and let it all hang out. When a child recognizes that there are different behavioral expectations for public vs. private, that is in fact a sign of maturity.

But this is why remote learning—school at home—presents a special challenge. The boundary between school (where he is civilized) and home (where he is still a baby) is blurred. He used to kick and scream at home, and then leave all that behind when he went to school; but what happens when school is held in the kicking place?

This semester, my wife and I chose to enroll our son in our district’s remote learning program. His third grade class meets via Zoom, and the teacher gives instruction while the students do their work in their own workspaces at home. My son has his own room, his own desk, and the school provided every student with an iPad. As I work from home, I am available to provide him with tech support, moral support, and lunch. We are incredibly lucky—incredibly privileged—to be able to do this, and we jumped at the opportunity.

In addition to being well-mannered, my son does well at school. He’s bright, intellectually curious, good at math, creative. The question was, can he provide himself with the same emotional armor at home that he instinctively knows to put on at school?

So far, it has not gone well. Even on his best days, when my son logs on to the virtual classroom bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and ready to work, he reacts strongly to the mildest setbacks. If the teacher calls on him when he isn’t ready. If she has to correct him, even slightly. If he isn’t called on at all. If a lesson feels too long or too short or too confusing or too boringly simple. The littlest thing is enough to make him wilt, turn off his camera, or just drop out of frame to pound the floor and cry.

And that is on a good day, after a good night’s sleep and a hearty breakfast. Other days, he can barely bring himself to log on at all.

My son is not a baby, and this is not his first year at school. In kindergarten, first grade, second grade, he learned to weather those storms, to put on a sort of emotional armor and survive those little setbacks. Remote school seems to have stripped away that armor and left him as vulnerable as he was on his first day of Pre-K.

fotostorm/Getty

Families all over the country are doing remote school right now—by choice or by necessity—and I wonder how many eight- or nine- or ten-year-olds across America have reverted to their nursery school selves. For many families, access to technology and WiFi are the main obstacles to remote learning. But even when these are in place, getting your child acclimated to this new and strange modality can be an uphill battle.

What is my role as the parent in this situation?

My first instinct was to comfort him, to hold him and kiss away his tears, and do some spontaneous problem-solving. What happened? What’s upsetting you? Are you having trouble with the assignment? How can I help?

The problem with this approach, of course, is that I would be casting myself as the hero in the story, and taking away the opportunity for student and teacher to solve the problem on their own. My son needs to be able to pick himself up, dust himself off and return to class—or, if he needs help, the teacher should be the one to provide it.

But the teacher can’t see him if he drops out of frame. She can’t hear his cries if the students are on mute.

In class yesterday, my son’s teacher asked the students to come up with personal anecdotes. This was basically a brainstorm that will eventually lead to a writing assignment. My son’s first thought was I don’t know what to write, and that just got stuck in his head.

This happens in writing classes all the time. Normally, the teacher would circulate throughout the room, peeking at each child’s paper, and whenever she sees a blank page, she would say privately, confidentially, “How’s it going, buddy? You need some help?” Then she would give him some prompts aimed at helping him get started.

Instead, my son kept just saying to himself, I don’t know what to write, I don’t know what to write, until he dropped to the floor. The teacher noticed he had gone off camera, and she called his name to ask where he was, but my son couldn’t summon the courage to answer. He was too upset. Hearing her call out to him only added to his feeling of frustration and failure.

No matter how nurturing, how caring the teacher may be, she is simply not able to respond to him the way she would respond to a crying child who is physically in her presence. Where there should be a sensitive, perceptive grown-up giving support, there is an empty space—the lonely four walls of my child’s room.

I don’t want to be a helicopter parent, but at some point someone needs to do something. Yes, my son should develop the skills to pick himself up off the floor, but he isn’t there yet. The hope, I guess, is that this experience will force him to toughen up. He’ll cry on the floor until he’s tired of crying, and then he’ll get up and get to work. My fear is that the opposite will happen: those feelings of dread and anxiety will only grow, to the point where that becomes his whole experience of school.

I think we should give remote school more of a chance before doing anything drastic. Even in the best of times, a new schedule or a new program requires a period of adjustment, and it has only been a few weeks. We are talking to the teacher, talking to the school psychologist, talking to our son. If my child can consider the home learning environment as equivalent to the classroom (he would not cry on the floor at school), maybe he can soldier through. Maybe there is more the teacher can do to support him. But it’s a problem.

The difference between public and private behavior is something children learn early in life. A child knows how to be a third grader at school, and then magically transform back into a toddler at home. But learning to be a third grader at home is an entirely different, and almost unprecedented, challenge. If your otherwise well-adjusted child is dropping to the floor and crying in the middle of a morning Zoom, keep in mind that the kid is just getting started in the process of adapting to school all over again—and you and your child are not alone.

This article was originally published on