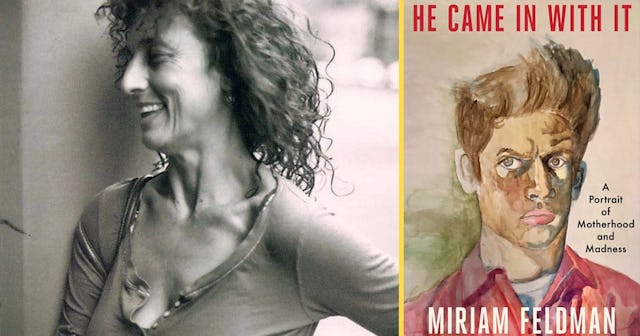

How Having A Son With Schizophrenia Prepared Me For A Global Pandemic

Having a child with serious mental illness is an exercise in loss and grief with no equal because it holds a particular irony … they are here, but they are gone at the same time. We do not have the closure of mourning, as with a death. They are lost to us and at the same time right in front of our eyes. Having a child with serious mental illness is like standing at the shore of a vast ocean you will never be able to enter.

But it is other things as well. It’s profound. It is shockingly beautiful, sometimes. And I know this isn’t politically correct, but sometimes it is really funny. We have to search meticulously for the joy, but it also can be found. The most stunning aspect is the constant uncertainty that will color the rest of my life. We are at the mercy of this disease and I never know what will happen next. Who will he be today? Will there be disaster or comfort? Will he take his meds? I face each new day poised for the unimaginable. A skill that is coming in very handy right now.

Courtesy of Miriam Feldman

Fifteen years into my son’s schizophrenia, I stand at the place where the sand meets the water, my bare feet planted firmly. I still cannot retrieve him, but at least he hears me now. I play a kind of call-and-response game with him, like Marco Polo. He will never lose me; I won’t allow it. The doctors and scientists haven’t found a way in yet, to his head. They do not even know what causes this. We tinker around with medications, environments, strategies … but the only surefire way to fight it is with the heart. Without love we are lost — another realization and subsequent behavior shift that is useful these days. These pandemic days.

I tried for so many years to find some sort of logic or system for what was happening. Where did it start? Whose fault is it? How can I fix it? Finally, I realized that none of that mattered, it was irrelevant, all that counted was what I did next. How I reacted. How I armed myself with knowledge, prepared myself for the worst. Now that I accept it is all out of my control, I can brace for the next wave. Sound familiar?

As I watch the news and listen to people talk since COVID-19 has consumed our lives, I feel an eerie recognition. All of a sudden it sounds like everyone has a son with schizophrenia. Everyone is scared all the time. No one knows what is coming next. We are all poised. We are all locked and loaded. The knowledge that anything can happen, and is happening, is a weighty apparatus to carry around.

It’s heavy. It’s so heavy, and I’ve carried it every day for fifteen years. The responsibility for my son. No one else can, will, shoulder it. I suppose that is fair. He is mine after all … my cells, my blood, my history. Lying in bed at night, I wonder what will happen when I am gone. What will happen to him? Who will do the laundry, make sure the surfaces are clean, remember his appointments? I don’t ever want to die and leave him all alone, and sometimes I want to die today and be free of it all. Wow. I said it. I have thought about my mortality and its repercussions every day for the past fifteen years. Now, everyone is thinking like this. We are all on the shore of the same vast ocean.

Courtesy of Miriam Feldman

I was out of town in the beginning of March, when the coronavirus shifted from insignificant to wildly relevant. I rushed from the airport to my son’s place, certain he’d be upset. He greeted me with his familiar, life-altering grin and said “Hi, Mama, did you have a nice trip?” As I gingerly broached the subject of the pandemic, I realized that he was completely unaware. It hadn’t even entered his universe. So, do I tell him? Does he need this information in his head? I thought about his lifestyle. He stays in his apartment most of the time, goes for walks, interacts with very few people: me, his caregivers. Thanks to a sprinkling of OCD in the mix, I doubt he’s touched a doorknob in a decade! He lives, quite contentedly (most of the time), in his own immediate world. He is the perfect quarantinee. His way of living embodies all the rules of social isolation and demonstrates how to navigate uncertainty. He takes it, literally, one day at a time. I decided to give him enough information to protect him, but not enough to scare him.

Schizophrenia is comprised of a million little things. An odd glance that can become something else altogether. A twitch or involuntary kick that tells the story of medicine and bodies. A glint of recognition, maybe the remembrance of love? Voices. There are voices in his head, certainly, but there are voices in mine as well. Singsong, sad, taunting, my own voices remind me that I must stay alert. I still have a slight edge of fear every time a phone rings, or there is a knock on the door, or a letter arrives. This constant, pervasive uncertainty is now shared by everyone.

How do we live with it? During the time when my son’s schizophrenia was out of control, I ran serpentine through my days, certain the end was near. But there wasn’t an apocalypse, it was just the new normal, and I had to get used to it. Let’s face it, we don’t have control over anything, anyway, that’s an illusion. The gift that my son’s schizophrenia gave me is the absolute understanding of that fact. I did have a choice, though. Do I continue to rail and lurch against the unknowable, the inevitable, or do I find my footing in the face of this uncertainty? The subsequent acceptance was the gift, and it has prepared me for what is happening now.

There is a particular beauty in all being in the same place at the same time, even if that place is terrible. Our stealth enemy does not know who we are and doesn’t care; we’re all the same to COVID-19. All. The. Same. Just stop and think about that for a minute. We stand (six feet apart, hopefully) at the shore of this unknowable ocean, certain of nothing other than the fact that no one of us is particularly different than the other. Hopefully, when we wake from this fever dream, we will remember that.

This article was originally published on