Teacher's Chart For Explaining Consent To Kids Is Spot-On

Her chart explains what consent means in terms kids can understand — and remember

As the country watched Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s brave testimony yesterday (and Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s yelling and crying), the topic of sexual assault has been a big one in the national conversation. That means your kids have probably heard enough about it to want to know more — but how do you even begin to explain sexual assault to grade schoolers? Well, it all starts with teaching kids about consent — which is exactly what one teacher’s brilliant guidelines aim to do.

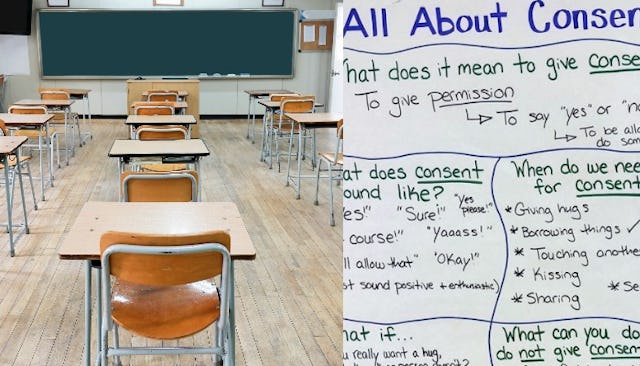

Elizabeth Kleinrock is a third grade teacher, but she’s much more than that. According to her website, Teach and Transform, Kleinrock is using her position in the classroom to teach kids about more than just math and reading. She calls herself a “social justice advocate” and “anti-bias educator.” In the wake of the Kavanaugh and Ford testimonies, Kleinrock shared a chart full of information to help teach kids about consent — and it’s brilliantly simple.

“Everything about Kavanaugh in the news has been making me HEATED,” she writes. “So whenever I get frustrated about the state of our country, it inspires me to proactively teach my kids to DO BETTER. Today was all about CONSENT. We even explored the grey areas, like if someone says ‘yes’ but their tone and body language really says ‘no.’ Role playing is a great way to reinforce these skills, but they MUST be taught explicitly!”

Hell. Yes.

First, she defines consent. Then, she gives examples of how it will sound when someone is saying “yes” — and what a child can say if they’re wanting to turn down someone’s physical contact. She also tells kids what kinds of things require consent in the first place, which is very helpful. So many little ones don’t understand that even friendly hugs are a no-go if the other party isn’t feeling it. Kleinrock also gives scenarios where it’s clear the other person isn’t wanting to be touched.

I have been discussing the concept of consent with my kids since they were old enough to have conversations, but I wish I’d had Kleinrock’s breakdown to help guide me a few years ago. It’s hard to zero in on the parts young children will truly grasp, and since their attention spans tend to be brief, long lectures don’t really work. It’s all about keeping things pretty simple and memorable — and as she points out, role play is also extremely helpful.

In an article for Tolerence.org, Kleinrock elaborates on how she teaches her third grade students about consent. “In elementary school classrooms, one of the first social emotional topics covered is the importance of keeping our hands and feet to ourselves and respecting others’ personal space. In early years, teachers redirect students to use their words to express themselves when having strong feelings, rather than using physical actions to get what they want. In these conversations and lessons, educators are already teaching the foundations of consent, and it is crucial to assign language to the concept of asking permission before touching anyone else’s body.”

Kleinrock also notes that when she broaches the topic with such young children, she’s not even thinking about sex. “Instead, we talk about safe physical interactions that occur daily in the classroom and outside at recess, and how to communicate your personal boundaries with those around you. We begin by defining the word consent and breaking it down to its simplest form,” she writes.

And doesn’t that make a ton of sense? You can’t start a conversation about consent with a kindergartner and come right out the gate with sex. We start with simply telling them the importance of keeping their hands to themselves. As they get older, the topic gets more complex — but those early years are so crucially important for getting the idea across that consent is always needed, even for just a quick hug.

She concludes, “As educators and adults, we cannot change the past, but we can teach our students strategies to change these outcomes in the future.”