We're Teaching Our Kids To Read The Wrong Way

I remember learning phonics as a kindergartner in the mid ‘80s. I remember learning consonant combinations, vowel combinations, and a litany of rules as well as a litany of exceptions to those rules.

Later, as a new mom reading everything I could get my hands on so I could be The World’s Best Mom, I kept stumbling across the idea that teaching phonics was unnecessary—that a more intuitive and less stressful way to learn to read was an approach called “whole language” instruction. The thinking behind whole language instruction is that, with enough exposure to literature, children pick up reading instinctively. If we sit with our child and read to them and point out the words on the page as we read, and do this consistently, our child will eventually learn to read on their own. Reading is a natural process, they suggested.

The idea made sense to me at the time, especially since so many experts advise us to get out of our kids’ way and allow them to explore and learn on their own. Many children thrive with “unschooling,” driven to learn by their own innate curiosity, so why wouldn’t this also work with reading?

Many schools today operate under this belief too, mostly foregoing phonics instruction and instead exposing kids to literature and giving helpful tips for how to guess words based on context.

The problem, though, with this hands-off, let-them-figure-it-out-on-their-own approach for learning to read, is that for the majority of kids, it doesn’t work.

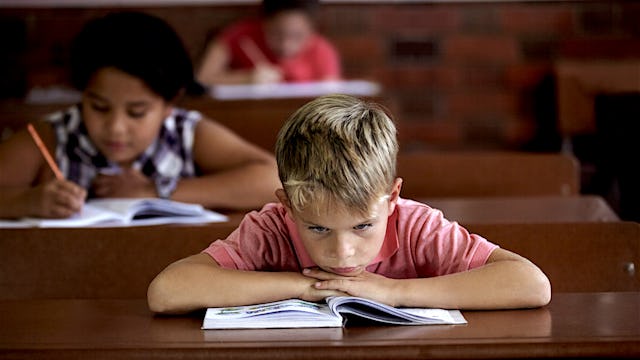

Our Kids Are Struggling

Millions of kids in the United States are not reading at even a basic level for their grade. Students often fall behind to the extent that they are recommended for interventions or assessed as having a learning disability, when in fact, the problem is that they have not received adequate and appropriate reading instruction.

And we’re not just talking about early grades where we might simply be seeing a variance in reading readiness. The National Assessment of Educational Progress reports that 32 percent of fourth graders and 24 percent of eighth graders are reading below a basic level. We’re sending a quarter of our kids out into the world without the most important tool they will ever use in their life—the ability to interpret the written word. This is unacceptable.

NPR followed Jack Silva, the chief academic officer for Bethlehem, PA public schools, for three years as Silva tried to figure out what the heck was going on in classrooms that left 44% of students in his district at a below-proficient reading level. What they found was earnest, well-meaning teachers using this whole language approach for teaching kids to read—a method they’d been instructed to use.

Take, for example, the following recommendation from a teaching textbook for how to teach a child to figure out a word they do not recognize in a text:

1. Read the whole sentence, cover up the unknown word, and guess at what word might make sense.

2. Uncover the first consonant letter(s) up to the first vowel, and make another guess at the word.

3. Uncover the whole word and ask students to see if the length of the written word matches the length of the spoken word.

4. Check to see if the consonants in the written word match the sounds in the word the student(s) have guessed.

There is so much wrong with this. Note the extent to which the child is prompted to guess. What if they guess wrong? Where do they go after that? This is not an effective way to teach a child the skills they need to read other words. In fact, this method often causes a child to misunderstand a text entirely, because they’ll guess a word that is close in sound and length to the actual word, but the word they’ve guessed has a totally different meaning.

Reading is not a natural process. Repeated studies have shown that children acquire reading skills best through what is called “synthetic instruction,” based on a scientific approach. Children need to learn to break down the components of a word so they can sound it out. This is called decoding.

Learning to decode requires systematic, step-by-step, graded instruction. English is an alphabetic language, meaning we use individual symbols that combine to make words. An important part of decoding is understanding how these letters work together to make different sounds, called phonemes. It’s not as simple as learning the sounds of each letter—it’s understanding that cat, hat, rat, and flat all have the same ending sound made with the same two letters, which leads a child to immediately recognize all words ending in “at.” This is called phoneme awareness, and it’s a powerful, scientifically tested tool that for so many children is the difference between reading success and reading failure. So why aren’t all schools teaching phoneme awareness?

Teachers Aren’t to Blame

Note that the above advice for figuring out an unknown word comes from a popular textbook. Between misguided advice like this and the popular notion that kids just figure stuff out on their own (it’s true for many things, but not generally for reading), no wonder teachers are struggling to get their students to read. The fact is, effectively teaching reading is a science in and of itself, and teachers need the proper training.

Remember Jack Silva, of Bethlehem, PA, frustrated that so many kids in his district were failing at reading? He instituted a district-wide overhaul, pouring millions of dollars into retraining teachers to teach students using synthetic instruction and focusing on phenome awareness and decoding. At the end of the 2018 school year, “84 percent of kindergartners met or exceeded the benchmark score. At three schools, it was 100 percent.”

Yes. We can do better. We must do better.

If you’re concerned that your school is lagging in this way, notify your school district. Be a squeaky wheel. This is a know-better-do-better situation, and now that we know, it’s time to do something. Because it isn’t our kids who are failing here. It’s we who are failing them.

This article was originally published on