How Much Does Violence In The Media Impact Our Kids?

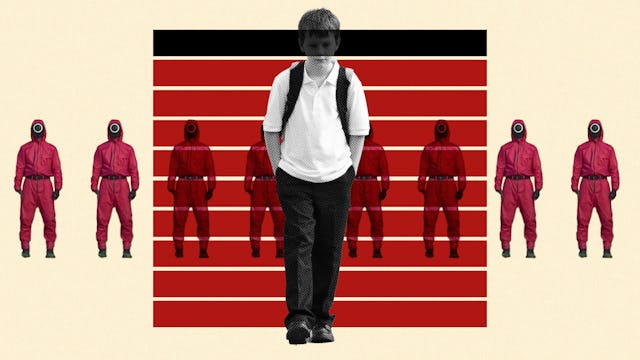

Just this week, my husband and I realized our daughter was witnessing pretty serious violence in the media without our knowledge. We were finishing up the new series “Squid Game” (which has been all the rage lately) when my daughter came downstairs after her bedtime for a drink. We paused the show, but as she looked at the screen and saw the faceless characters wearing red masks, she asked with a tone of familiarity, “Oh, you guys are watching ‘Squid Game?'”

My husband and I looked at one another, each of us stunned that our seven-year-old somehow knew about such a brutal show when we never watched it around her or our other children. So we did what any parent would do: we asked her where she heard or saw this show. She told us that someone on her bus had been playing a Roblox game built upon the basis of the Netflix series.

And of course, neither my husband nor I was surprised to hear about this kind of content on Roblox’s platform. Sure, Roblox can be a great place to find interactive games for kids. But, it’s home to some violent ones too. And while violence in the media doesn’t make a child inherently violent, it can be a risk factor.

To better explain it, some researchers use the link between lung cancer and smokers to paint a better picture of the association between violence in the media and violent children. Although not everyone who gets lung cancer is a smoker, smoking does make one more susceptible to lung cancer. Likewise, not all kids who witness violence in the media will become violent, but it makes them more prone to those kinds of responses.

But it goes beyond children modeling destructive behavior displayed on media. Emotional maturity doesn’t peak until the tween years, and kids younger than that often don’t have the mental or emotional capacity to differentiate fiction from reality yet.

“With toddlers and preschool-aged children, everything can seem much more immediate — and so seeing violence on TV can leave them feeling like their world is a scary place, where things like that might happen at any moment,” Michelle Garrison, an investigator at Seattle Children’s Research Institute Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, says. “In our research, we’ve seen that sleep problems like nightmares and trouble falling asleep go up in preschool children even when the violence they’re seeing on TV is comic cartoon violence, suggesting that there really isn’t such a thing as ‘safe media violence’ at this age.”

According to a recent study, violence in the media also increases the risk factors of developing “aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, and aggressive affect” and can decrease empathy and social skills. Researchers who study consequences brought on by violence in the media believe this “black-and-white” view promoted by the TV industry can distort how children perceive the real world.

“If a child sees himself as the ‘good guy,’ then anyone who disagrees with him must be a ‘bad guy’ — and this black-and-white thinking doesn’t leave much room for trying to see it from the other side, or working out a win-win compromise,” says Garrison, “On the other hand, if a child starts seeing himself as a ‘bad guy,’ then it may no longer feel like it’s about choices and actions that can change.”

Some have drawn comparisons from Marvel’s superheroes, Batman, Superman, Spiderman, etc. They all have a hand in shaping violence in the media, but these actions are usually towards villains. So because these protagonists are the “good guys” of the story, parental viewers often feel that their actions are readily justifiable to children. Unfortunately, most kids don’t have the proper range of cognitive or emotional capabilities to comprehend that concept yet.

And although opposing viewpoints are out there, many experts hail these analyses the act of “cherry-picking convenient data.” For example, one study conducted by Christopher Ferguson, a professor and co-chair at Stetson University, declared that although children may reenact violence when role-playing, that doesn’t mean that they will grow into violent people. Many disputed the claim, including Dan Romer, the University of Pennsylvania’s Adolescent Communication Institute director.

“The authors have a very simplistic model of how the mass media work, and they have an agenda that attempts to show that violent media are salutary rather than harmful,” Romer said.

It’s unrealistic to think that we can shield our children from violence on all streaming platforms, especially in the day of age that we live in now, where technology plays an integral part in day-to-day life. But there are ways for parents to limit the probability of their children witnessing on-screen brutality.

Studying TV and video game ratings/reviews is always a solid place to start. If parents witness something unsuitable for children, usually they are quick to raise awareness of those issues for others. Besides, parents who intentionally involve themselves with their children’s devices are better “in the know,” can bond over streaming and gaming interests, and have more opportunities to explain the differences between right and wrong as they arise.

Parents can keep a closer eye on these areas by implementing a rule that children can only use their iPad or tablet in a shared room of the house. Of course, some kids might prefer a bedroom to stream on their devices, but that has the possibility of offering more free rein than they can handle — especially for younger kids. By making sure a parent is always nearby, there will be more chances to use discretion. In addition, when parents take the media world out of their child’s bedroom, they preserve the tranquility of their child’s bedroom and ensure that it stays a safe space free of violence in the media.

If children try to stray away from screen-time rules and the excuse seems more than just the need for a different location, parents need to be aware of these red flags. For example, suppose they display signs of obsession, lose interest in other activities, or exhibit extreme bouts of anger surrounding iPad-related issues. They might hide or become secretive. In such cases, these issues may signal the need for more parental supervision, less screen time, or outside help from a physician.

There’s no doubt that, even when taking every precaution, our kids will still view violence in the media. And when they do, parents need to see that as an opportunity to discuss real-world consequences and healthy responses.

This article was originally published on