What NASA Taught Me About Death

When I was in college, I went to Paris for two weeks with my boyfriend. As we walked down la Rue de Something, two little girls and their mother walked toward us, but I was able to take in only the older one, wearing the same type of smock dress Melissa used to wear. The richness of her brown hair, how it parted and the specific textured ends resting like spears on her back were so particular to Melissa, I was startled. I looked at her as she locked eyes with me, and as we passed one another, I turned to see that she’d also turned, and was staring at me, her eyes haunted by recognition. I was so shaken I called my mother, who wondered aloud whether the girl I’d seen was Melissa’s sister. As it turns out, Melissa’s mother Sharon had moved to Paris, and now had two little girls, one of whom would be Melissa’s age.

A few years later, while I was still in college, my friend from high school Ayrev died when he fell asleep at the wheel. On November 20th, 1992 (the same day I am writing this), my stepfather died of a heart attack, and in my late twenties my best friend Stephen died of AIDS. I looked for signs of them everywhere, but saw no alternate versions of them as I had with Melissa. They appeared in my dreams, but never in the people I passed on the street. Sometimes I’d hear Stephen’s laugh come from someone else’s mouth, or recognize Ayrev’s stooped walk in someone else’s gait. Reminders, but nothing more. In February 2014 my friend Maggie died, and then this past April my grandmother, “Puggy,” died at age 94.

Puggy was no regular grandma. First of all, she wouldn’t allow anyone to call her “grandma” since it made her feel old. She was Peggy to her friends, and she became Puggy to her grandkids, and soon to everyone else. She had grandma tendencies though. She collected suns and rice jars, but she was most well known for her vast collection of Little Red Riding Hoods. She’d amassed so much memorabilia, she dedicated a room in her apartment to the fairy tale. Every occasion was an occasion to give Puggy a Little Red Riding Hood collectible, and everyone gave with the intention of “winning.”

She was the most social person I’ve ever known (my mother comes in second). She saw every movie, every play, and ate lunch and dinner out every single day—except Sunday. When you called in the beginning of November to make dinner plans, she’d consult her book and offer the first available date she had, in January.

The last day of her life was no different from any other of her days, except for the fact that it ended. She got up, wrote a letter to Mia, my 8-year-old niece, and her great-granddaughter, went to lunch with Sue Ellis, returned home with half a sandwich for Agnes, her housekeeper, and went into her bedroom to phone Sue Ellis to thank her for such a lovely time. They made another date and Sue Ellis hung up the phone, but Puggy never did. When Agnes came in, not five minutes later, to give her the mail, she was dead, sitting on the side of her bed, feet on the floor, phone still in her hand, mouth open and leaning back on a pillow. Puggy died at age 94 on April 16, 2014, while on the phone. She died social, just how she lived.

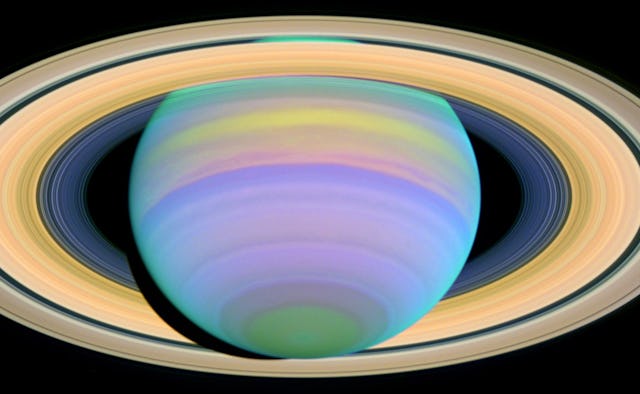

I didn’t have time to look for her in the world because the night she died, NASA found her. My brother alerted us all to their discovery, with an email whose subject read, “The most bizarre thing ever.” Puggy’s death coincided with another once-in-a-lifetime event: Saturn gave birth to a new moon, and NASA named it Peggy.

That same day, the announcement came out:

For the first and perhaps the last time ever, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, whose mission is to orbit Saturn, has captured a new moon emerging from the jovian planet’s rings. As you might know, the birth of a moon is an extremely rare event, and in Saturn’s case, it might never happen again.

I don’t believe in an afterlife, or in heaven. I believe our atoms are recycled and go into some big atomic mixing barrel and together they commingle and create new things like sea otters and iPhones. My grandmother is gone. The physical person she was will never be again, but I’d like to believe it’s not just coincidence that her death coincided with the rare birth of a new moon that shared her name. I’d like to believe that in everything is someone who came before, that Melissa and Maggie and Puggy and everyone else I’ve lost are now new shaped entities. That way everyone I ever meet, and every moon I ever see, will always contain the possibility of being someone I loved, who loved me.

NASA taught me to look at the world and wonder about things in a more concrete way. It gave me hope that life and death aren’t completely separate acts, and that the world we live in doesn’t do away with those who die, but recycles them as moons and planets. Now I understand, in a richer, more complex way, why Puggy loved fairytales so much. Is my grandmother looking down on me? Probably not, but it sure makes life more meaningful to look at the night sky and imagine her there.

This article was originally published on