When Should I Tell My Daughters That I'm Not Their Only Mom?

My 6-year-old daughter, Alana, woke me up that morning with smiles and hugs: “Mommy, Mommy, Mommy! Happy Mother’s Day!” My 7-year-old daughter, Sophia, was close behind her, holding a single red rose with a card she’d made herself. This was the morning I had dreamed about since I was 10-years-old, when I knew for sure I wanted to be a mom.

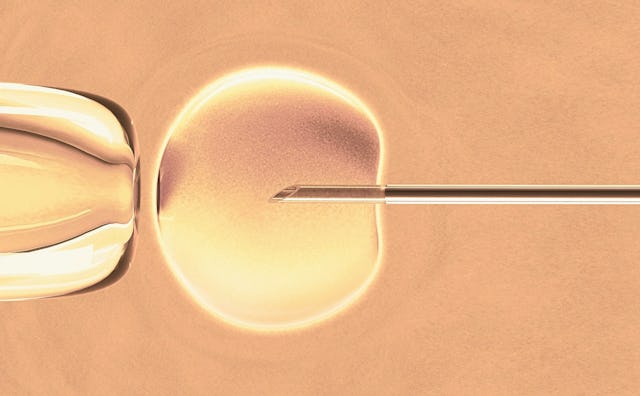

My journey to this day wasn’t easy. It took me forever to figure out how to date well enough to get married. Then, my husband, Sean, and I spent the next five years in deep relationships with various fertility clinics. We ended up at the best fertility clinic in the world, flying from Austin to Denver for routine exams and complex procedures.

The first step in Denver was a series of tests on my reproductive cycle, and the results weren’t good. I was 38 and my eggs were too old. They were very unlikely to lead to pregnancy, naturally or with medical assistance.

It’s a strange kind of mourning when you mourn for your DNA. It isn’t about a child that you have known, it’s about children you will never know. It isn’t about not being a parent at all—it’s about not holding a baby that looks at least a little like you. It’s about not having a kid who shares subtle qualities and mannerisms with your relatives or an adult who will carry a little part of you after you are gone.

We call my girls’ DNA Mom “Pam.” We didn’t have her real name or a picture, just a two-page description that was mostly a medical history. She was an office manager, so we named her after Pam on The Office. She liked dolphins, so we bought her a sculpture of two blue glass dolphins in mid-jump as a gift of appreciation.

On Mother’s Day, Sophia brought me Nutella toast and coffee in bed, two of my favorites. Alana gave me a few hundred hugs. The girls played with their cousins. I spent time with all the moms in our extended family. Everyone, ages 6 to 77, played kickball in the backyard with made-up rules and lots of laughing. This was more of the day I had dreamed of. But I was thinking, in part of my mind, that I would tell my girls about Pam soon.

A few months ago, Sophia’s older friend did her science fair project on dominant and recessive genes. I told her mom, only halfway kidding, “Don’t let my girls see that!” My girls both have blue eyes. Sean’s are blue, and mine are brown. What are the statistical chances of that, given our DNA?

On some nights, as we snuggle right before bed, I tell my girls their birth story. I tell them that their dad and I wanted to be parents very, very much, but that it wasn’t easy. We had a very good doctor all the way in Colorado, and we took planes into the snowy mountains to get his help. We told them there was a special woman who helped us, too. We are so grateful for these people’s help because now we get to be Alana and Sophia’s mommy and daddy.

We have been open about our IVF and donor egg experience with family and friends. But we haven’t told the girls the details of just how the woman helped us.

First of all, the explanation requires an understanding of how the egg and the sperm make a baby, which is a lot of information at their age.

But most of all, it is because I don’t know how to tell them they have a DNA Mom who isn’t me. Will they wonder what she looks like? Will they want to know more about her? Will they miss her, even though they have never met? Will they feel distant from me, subconsciously, because they are more aware of our physical differences?

If we tell them too early, will they be confused and sad? If we tell them too late, will they think we have kept an important secret from them?

By next Mother’s Day, my girls will know more. We will have many conversations over time, based on their questions and what makes sense for their ages. I’m proud of my family. I’m proud of my girls. I can’t wait for all the Mother’s Days to come.

This article was originally published on