You Asked, I Answered: 7 Difficult Questions About Racism

Recently, I posted an article titled, Why I Will Never Walk Alone, and I have been blown away by the incredibly kind and heartwarming responses that I have received. This has been a rough week (for, hopefully obvious reasons), but many of your words have strengthened my faith in the goodness of humanity. I cannot thank you enough for that.

After my article was posted, I received a metric ton of messages, and unfortunately, I cannot answer all of them. However, there have been some themes that I’ve noticed in some of the questions that I’ve received, so I’m going to answer the seven most common ones below (or more accurately, I should say that I’ll provide my opinion).

If you haven’t already read the article, Why I’ll Never Walk Alone, please start there first. If you’ve already done that, feel free to read the questions below, or scroll down to the one that interests you the most.

Either way, there’s a lot of work to do, so let’s jump in:

1. “If you’re so scared to live in your awful neighborhood, why don’t you just move?”

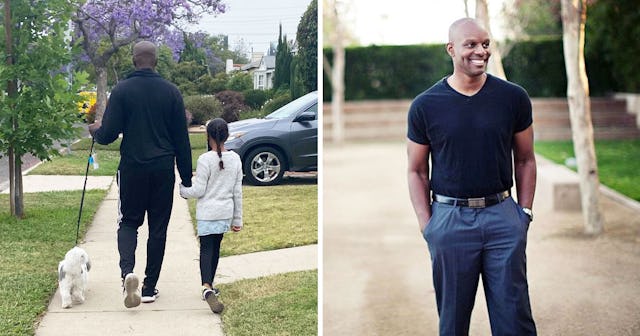

Courtesy of Shola Richards

I never said that my neighborhood is “awful”—if anything, it’s just like pretty much any neighborhood in America. What I did say though, is that I would be scared to walk alone in my neighborhood.

I absolutely love my neighbors on my street, and many of them who live in the houses near me are now personal friends of mine. But since I live in Los Angeles, as you can imagine, I don’t know ALL of my neighbors within a three-block radius (and they don’t know me).

In the past couple of years here, when I’ve taken longer walks with my dog (off of my street where people don’t know me), I’ve had people literally run across a busy street just so they wouldn’t have to pass me on the sidewalk. When my dog is sniffing around in front of a random house looking for a place to pee, I’ve noticed people peering through their window shades watching me with their cell phones pressed to their ears. I’m not a threat to anyone. I’m simply trying to exist and get some fresh air. These experiences aren’t uncommon for Black men, and it’s difficult to explain the “death by a thousand paper cuts” feeling that we have to endure because of it. Additionally, as an HSP (Highly Sensitive Person), it’s more than exhausting—it’s soul destroying.

Not to mention, what I described above was what happens when I’m with my ridiculously adorable dog and/or my equally cute daughters. But if I were alone, walking up and down streets that I don’t live on, just to get some fresh air (in my cloth face mask, mind you), it’s very possible that I could be targeted by an overzealous homeowner or a police officer. And yes, that scares the living hell out of me. My primary objective of this lifetime is to be ALWAYS be there for the ladies in my life (my wife and daughters), and I’m not willing to do anything that could jeopardize that. That’s why I will always be with my girls and/or my dog whenever I’m walking around in a residential area that’s not on my street.

(And if you’re thinking, “well, if you don’t want to look threatening, then stop wearing a mask,” sadly, you completely missed the point.)

2. “I always respond to Black Lives Matter by saying ‘All Lives Matter.’ Why shouldn’t I do that?”

Courtesy of Shola Richards

Let me put it this way: if I broke my ankle playing basketball, and I went to the doctor for medical attention, and his response to my pain was, “ALL bones matter” and then sent me home, that would be pretty dismissive (if not, outright malpractice) right?

Yes, my ribs, my wrist and my skull all matter—that’s obvious. But right now? It’s my effing ankle that’s broken and in need of immediate attention. This is not the time to bring up any other bones, because at this moment, only one bone is in crisis.

I know that some people learn concepts easier through metaphors, and this is the best I can do at the moment.

But putting the metaphor aside, here’s the bottom line: all lives can’t matter until Black lives matter.

3. “I get that people are upset right now, but how is rioting helping your cause?”

Courtesy of Shola Richards

Fair question. Let’s break this down.

I’m sure that we can agree that there is a troubling trend of unarmed Black men and women being killed by police, no? Similar to Kübler-Ross’ stages of grief, I’m going to create “Shola’s levels of outrage” (please don’t bother Googling it, because it’s not a thing):

Level 1: Trusting the authorities to step up and do the right thing by prosecuting and convicting police officers who kill unarmed Black people (ineffective).

Level 2: Gathering in large groups to peacefully (and rightfully, loudly) march and express our displeasure that these atrocities continue, unchecked (also, at this point, not very effective in changing anything).

Level 3: Famous athletes taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality against Black people. This was wildly effective in gaining attention, but sadly, the narrative was quickly hijacked when people called that peaceful protest “Anti-American,” “Anti-military,” and “Anti-flag,” even though none of which were true. As a result, people forgot the purpose of this protest (which again, was solely to protest police brutality against Black people), and we’re still stuck at square one.

Level 4: Rioting. After praying for change, after begging law enforcement to do the right thing, after yelling at the top of our lungs in countless marches, after watching a highly-publicized effort to bring attention to this issue fail, due to having the narrative hijacked…nothing has changed. Black men and women are still being killed by police. We are outraged that our lives seemingly don’t matter. We are outraged that the men and women we love as husbands, wives, sons, daughters, brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, and friends could die, without any repercussions. Most of all, we are outraged that the basic human need of being heard has not been met. Literally, nothing has worked to get our voices heard, so now we’re taking matters into our own hands. The years of frustration, sadness, fear, and exasperation has boiled over into pure, unadulterated outrage. Imagine being driven to a level of madness that you would be willing to break the law in order to be heard. Keeping it real, I’ve been driven to madness by these recent events too. But since I’m a lover, not a fighter, it has been expressed by not eating, feeling constantly sick, and suffering many sleepless nights.

This is NOT a justification for rioting, obviously. Again, let me be clear (excuse the caps, but I need this for emphasis so my words don’t get twisted), RIOTING AND LOOTING IS ILLEGAL AND SHOULD BE PROSECUTED. And obviously, so must the crimes that inspired the riots in the first place (i.e., the police brutality against Black people).

You don’t have to agree with rioting, but hopefully this will provide some additional clarity as to why it is happening.

As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “a riot is the language of the unheard.”

4. “I don’t see color in people, and I consider myself colorblind. What’s wrong with that?”

Courtesy of Shola Richards

A lot actually. To be clear, I’m not referring to people who have a vision issue that makes it difficult to distinguish certain colors—that would make me a total jerk. No, I’m talking about people who think that it’s a positive trait to be “blind” to other races and cultures.

The most damaging aspect of colorblindness is that it encourages us to put our collective heads in the sand and pretend that our differences do not exist. But here’s the thing—if you don’t see my race, my culture and my heritage, then how could you really see me?

I am Shola Mark Richards—the son of a West African man and a Mississippi woman, and I am very proud of who I am. My life as an African-American man has brought me my own stories, struggles and joys (many of which, I shared on this page), and I want you to see that. For us to connect in a meaningful way, I need you to see that. Our connection becomes deeper by acknowledging (and ideally, learning from) the differences of others.

5. “I still don’t understand the concept of white privilege. What is it that I can do as a white man that you cannot?”

I’ll share with you a recent example.

One of my very well-meaning neighbors was out of town, and some Amazon boxes were piled up on his front porch. He texted me to see if I could head over to his house, pick up the packages, and bring the packages back to my house until he returned home (I’m sure that you know where I’m going with this).

The thought of me going to a house that was not my own, grabbing a bunch of packages that didn’t belong to me (remember, in a cloth mask), and then walking them back to my house was NOT going to happen. Even though he meant well, it is easy to see how that could have ended up poorly for me. As a white man, you probably wouldn’t have thought twice about that request, but for me, I have to think about those things every day of my life.

Like I said in my earlier post, white privilege doesn’t mean that your life isn’t difficult. It simply means that the color of your skin isn’t adding to your difficulties.

6. “I’m so tired of listening to Black people being outraged about a few bad cops killing Black people. Where is the same outrage about Black-on-Black crime, which happens way more often?!”

Courtesy of Shola Richards

Out of all the questions on this list, this is BY FAR my least favorite, because it’s rarely (if ever) asked in good faith. However, I’m happy to answer it in hopes that it will never be asked again…fingers crossed.

First, the facts. Black people kill other Black people at an extremely high rate. This is indisputable. About 90% of Black murder victims were killed by Black assailants. But here’s something else that’s equally indisputable: White people kill other white people at a similarly high rate. About 84% of white murder victims were killed by white assailants. This makes obvious sense because the majority of violent crimes are committed against people who they know. This information is important to keep in mind as I address this question.

Speaking of which, there are three reasons why this particular question makes no sense:

As mentioned above, it willfully neglects the fact that most violent crimes are intra-racial (Black-on-Black, white-on-white, Hispanic-on-Hispanic, etc.). That’s why bringing up Black-on-Black crime whenever a cop kills an unarmed Black man is so frustrating. It’s simply NOT relevant, and it serves only as a distraction from the real issue. Put it this way–if a Black man killed a white person in cold blood, and people started asking, “I’m sorry for your loss, but where’s your outrage about the abundance of white-on-white crime in our country?” That would be both insensitive and ridiculous. The same applies here.

Back in question #3 above, I described my four “Levels of Outrage.” Interestingly enough, when Black people commit violent crimes, it rarely needs to pass Level One. That’s because in those cases, they are routinely prosecuted and convicted for those crimes. The same cannot be said for the police officers who kill unarmed Black men.

Why would anyone think that Black people aren’t outraged when their loved ones are killed? Does anyone truly believe that we are only outraged if a cop kills a loved one, but if another Black person kills a loved one, that’s somehow okay? Come on. More importantly though, unless you have lived in the communities where Black-on-Black crime happens, you are likely unaware of all of the programs, initiatives, marches, and unceasing activism to reduce the crime in those communities. Unfortunately, gang counseling meetings for at-risk teens usually don’t make the national news. But to say that we aren’t outraged by any violent crime against our loved ones (no matter who does it) is not only a wildly uninformed take, it’s actually pretty insulting too.

7. “What do you mean that reverse racism is not real? I know many racist Black people, and you’re kidding yourself if you don’t believe that’s true.”

Black people can most definitely be prejudiced (and yes, I know a few), but no, we can’t be racist (or reverse-racist, for that matter).

Not to get too deep into this, but racism is much more than prejudice. Racism also requires systemic power that comes from a long history of being a racial majority. That long history of prejudice mixed with systemic power has affected PoC’s lives in many undesirable ways (including, but not limited to, affordable housing, the justice system, educational opportunities, promotion opportunities at work, credit worthiness, media portrayals, and treatment by law enforcement to name a few).

So, when/if you hear anyone start whining that Black History Month, Black Entertainment Television, the Diversity & Inclusion training you’re required to take for work, or the Black Panther movie are examples of reverse-racism, please kindly ask them to take several seats.

That’s all that I have for now, friends. If you read this far, then you are obviously very serious about learning more and being a strong ally, and I appreciate you so much for that.

There is a lot of important work to do, and I’m ready to walk with you as we heal this world, together.

Ubuntu ❤️.

This article was originally published on