That Sadness And Anger You're Feeling? There's A Reason For It

During the early days of the pandemic, I spent a lot of time starting out the window. Unable to get my footing, I felt constantly adrift. I had trouble making decisions, about everything from what restaurant to order carryout from to whether I should buy an exercise bike to major career decisions. When I did make decisions, they often seemed like the wrong one or they were out of character. There was a constant sense of fear and dread.

After a truly awful fall and a languishing winter, things seemed to take a turn in late spring. At first I was skeptical. Then I was hopeful and, dare I say, optimistic that the worst was behind us.

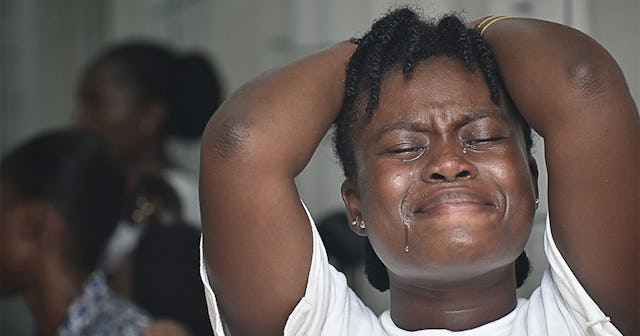

But soon enough, that all unraveled and with it came a crashing waves of rage. Pure and utter rage.

I’m not just sad — I’m downright livid. I spend all day, every day, battling a fury that is simmering just below the surface.

But the surface looks fairly calm, delightful even. My family is healthy and as vaccinated as we can be. We live in an area where masks are mandated in schools and public places, which somewhat calms my fears. I have work that is both satisfying and flexible. My marriage is strong, and I genuinely like being around my husband all day.

So what’s the problem, you might ask? Well…. <<waves hands at the entire world>>, everything.

I spent the early days (okay, more like months) of the pandemic in a daze. I was confused and exhausted. I couldn’t figure out what day it was and had no real sense of what I should be doing. Should I be cleaning my closets? Napping? Working on my resume? Taking another little fucking walk?

The brain fog eventually subsided to full-blown anxiety and an unshakable funk. It felt odd to admit that I was struggling so much, because most days I moved through life somewhat seamlessly. I did my job and I volunteered a bit. I folded the laundry and cleaned the kitchen. I texted with friends and got in some exercise every day. I learned to find the silver linings in these wild and weird times, things like the lack of Saturday morning sports activities and watching a Netflix show with my kids while they were on lunch break. But even those silver linings were heavy with some kind of amorphous dread.

When people would ask, “how are you?” I considered: Do I tell them that I’m so beat down from quarantine fatigue and next-level crazy conspiracy theories and Americans who don’t actually care about each other that I want to scream so loud only dogs can hear and cry my eyes out for hours? Or do I tell them that I’m so freaking grateful that we have our health and our family is safe and I work from home and my kids are relatively happy even though their life has been flipped upside down and we have a comfortable home and I have strong relationships with my family and friends that I want to shout with joy and cry tears of happiness? Ultimately, I was too exhausted and beat-down and sad to respond with anything other than, “I’m fine…I guess.”

And now, here we are almost a year later, and I still feel the same.

Because the thing is, despite the blinding rage I feel right now and the intense disappointment that the pandemic is as bad as ever, I am shockingly and almost embarrassingly … happy. Which really just makes the clusterfuck of emotions all the more confusing.

How can I be so angry and sad when my life is so good? It seems illogical and cruel, like I’m doomed to be some Debbie Downer carrying an Eeyore-like cloud of rain with me. So what’s the deal?

Ambiguous loss: That’s what.

In the early stages of the pandemic, there was a lot of talk about grief. We were grieving the loss of normalcy, the loss of a sense of security, the loss of social interactions and connections, the loss of jobs and life. The list goes on and on.

A year later, we are still facing those losses. For many of us, especially those of us who are HSPs, we’re also mourning the loss of our faith in humanity. Call me naïve, but I’ve always believed that most people are mostly good most of the time. The realization that this might not be as true as I thought — or dare I say, true at all — has rocked me to my core. But is that even something you can mourn? The loss of our faith in humanity? The loss of normalcy? The loss of a belief that people actually cared about each other?

Turns out it is not only something that we can mourn, but according to an article in Forge for Medium, because these are ambiguous losses, we also run the risk of getting stuck in them.

“What we have now is a pile-up of losses that are unidentifiable,” Dr. Pauline Boss, who developed the theory of ambiguous loss, told writer Jude Ellison S. Doyle. “They’re unverified. For example, loss of trust in the world as a safe place. Loss of our routines… On the most extreme side, there’s loss of being able to see a loved one when they are very, very ill or dying.”

Ambiguous loss has been so pervasive over the past 18 months that Dr. Moss recently published a new book, The Myth of Closure: Ambiguous Loss in a Time of Pandemic and Change.

“That pile-up of loss can be debilitating because ambiguity short-circuits our ability to move on,” writes Doyle in Forge. “Most grief subsides naturally over time, but when the loss is uncertain, grief becomes ‘frozen,’ stuck at the same pain level indefinitely.

To get unstuck, Moss suggests, that we let go of the expectation of closure. “There is no closure on any losses that we have experienced,” she says. “It’s more like a patchwork quilt.”

Instead of trying erase the sadness, Moss suggests trying to create purpose out of our grief. To be honest, this seems a bit daunting to me right now. Last spring, I dealt with it by booking vaccine appointments for family and friends, but now, I’m having trouble figure out how to craft all this anger, loss, and grief into something purposeful. I’m not a healthcare worker, I’m not a therapist, and I’m not an essential worker. I’m just a writer, a mom, a wife, and friend who’s having trouble navigating the emotions of it all.

I hope to eventually figure out how to make something meaningful of this tragic time. I hope that we all can, that we can start to heal. In the meantime, maybe this essay will make someone else feel a little less alone.

I suppose that’ll have to be enough for now.

This article was originally published on