10 Under-Represented Black History Figures You Should Know

For as long as I can remember, we have always learned about the same handful of black people during Black History Month. It’s bad enough that our entire history is being distilled into the shortest month of the year, but then to just recycle the same 10-ish people every year for the rest of time — how is that learning about black history?

There are so many black people who have contributed to this country that it’s impossible to name them all. This list is by no means complete, but these are people who were agents of change and don’t get their rightful credit for everything they did to move history forward.

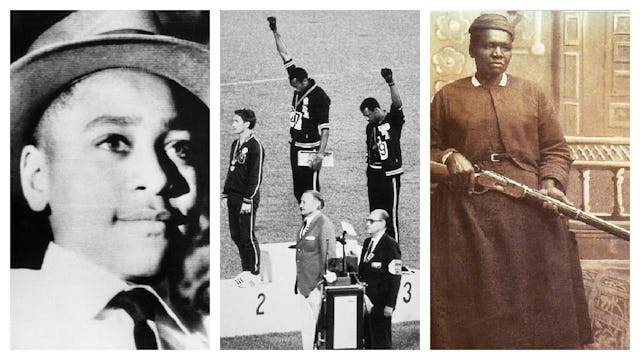

Emmett Till

Long before Trayvon Martin or Tamir Rice, there was Emmett Till. In the summer of 1955, Emmett Till was visiting family in Mississippi from Chicago. Though the exact details of what happened are long disputed, allegedly Till whistled at or spoke to a young white woman who was working at a small store. What was to come was one of the most horrific hate crimes in modern US history.

A group of white men descended on the home of Till’s family in the middle of the night several days after the incident, dragging the 14-year-old boy out of bed. They then brutally beat him, shooting him in the head and mutilating his body before throwing it in the Tallahatchie River. His body was found three days later.

Naturally, the men were acquitted. His mother chose to have an open casket funeral, so everyone could see her son’s bloated, mutilated body. In many ways, Till’s death was one of the catalysts for the Civil Rights Movement.

About 10 years ago, the woman at the center of all admitted things did not go down the way she testified they did in court.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw

Modern feminism would be lost without Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw. In 1989, she introduced the concept of intersectionality — the idea that overlapping identities, especially minority identities, relate within the structures of oppression, systemic mistreatment and discrimination. While intersectional feminism is still being disputed 30 years later, it is not a new concept. It’s just that Crenshaw gave it a name, therefore pushing it to the front of the conversation.

She is a full-time law professor at both UCLA and Columbia Law School and teaches classes that focus on race and gender issues. And back in 1991, she was part of the legal team representing Anita Hill during the Senate confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. Despite her busy teaching schedule, she is very active in current events and is often a contributor and organizer for things like #SayHerName and My Brother’s Keeper initiatives.

Dr. Pauli Murray

While Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw is the person who coined the term “intersectionality,” Dr. Pauli Murray probably displayed one of the most direct early versions of it. Murray, a lawyer who focused on civil and women’s rights, argued that the Fourteenth Amendment not only forbade racial discrimination, but also discrimination based on sex. This was argued in the memo “A Proposal to Reexamine the Applicability of the Fourteenth Amendment to State Laws and Practices Which Discriminate on the Basis of Sex Per Se.” Her work on the matter was so profound that Ruth Bader Ginsburg used it in her 1971 case Reed vs. Reed, giving Murray a co-author credit for her previous work.

Dr. Pauli Murray, who was openly in relationships with women for most of her life, had to fight racism and sexism at every turn. When she wanted to attend the University of North Carolina for law school in the late 1930s, she was rejected because of her race. Murray was active in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, openly criticizing the organizers of the 1963 March on Washington for excluding women from speaking or being on the board.

In the 1970s, she became the first ordained black female Episcopal priest. She died in 1985 of stomach cancer.

James Baldwin

James Baldwin was always outspoken — during a time when being unapologetically himself was beyond dangerous. Baldwin, who was black and gay, wrote extensively about both of those experiences in his works — both essays and fiction. His first book of essays, Notes of a Native Son deals mostly with what it means to be black in America in the 1950s, which was before the Civil Rights Movement really got off the ground. He also writes about his experience as a black man in France, where he would eventually move later in his life.

His second novel, Giovanni’s Room, was controversial because it spoke openly about gay men and their lives in a time way before Stonewall. During the 1960s, Baldwin was very active in the fight for civil rights, his work often heralded for its sharp critiques of white racism and eloquent expression of the real day-to-day challenges of what it means to be black in America. For many reasons, he was on the FBI watchlist for over approximately 10 years. When James Baldwin died in 1987, he left behind an unfinished memoir called Remember This House about his time with murdered civil rights activists Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. In 2016, the manuscript became the basis for the documentary I Am Not Your Negro.

Stagecoach Mary (Mary Fields)

Mary Fields is really the epitome of black girl magic. Born a slave in the 1830s, after being freed when slavery was ruled unconstitutional, she went on to become the first black woman star route mail carrier. Her life before becoming a star route carrier is just as interesting. She established herself in Cascade, Montana and worked at a mission hauling freight, farming, and doing laundry before eventually becoming forewoman.

Mary Fields was truly fearless, and it was a fight with a male subordinate (that involved gun play!) that ended her time at the mission. So, at approximately 60 years of age, Mary Fields put in a bid to be a mail carrier for the United States Postal service. Now star routes are obsolete, but in 1895, they were crucial. Fields put in the lowest bid and quickly assembled a team of six horses and a mule.

Her nickname, “Stagecoach,” came from her unwavering reliability — she never missed a day, and if the snow was too deep, she would strap on her snowshoes and deliver the mail by carrying the sacks on her back. She retired in 1903 when she was in her early 70s. She remained beloved in Cascade until she died in 1914.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Before there was Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry or Johnny Cash, there was Sister Rosetta Tharpe. While she started out singing gospel music, she eventually crossed over into early rhythm & blues and rock & roll. A guitar playing black woman? And one who rocked hard? Virtually unheard of.

Her way of distorting her electric guitar pioneered electric guitar playing. And aside from the previously mentioned artists, she also had a profound impact on British rock icons including Eric Clapton and Keith Richards. Sister Rosetta Tharpe was credited with not only being the one to give Little Richard the stage to become a performer, but also as Johnny Cash’s favorite singer. However, when she died as the result of a stroke, she was buried in an unmarked grave.

In the last 20 years, she has gained more attention — she was a postage stamp in 1998 and subject to several documentaries. But thankfully, Sister Rosetta was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018 as an early influencer, cementing her place in rock and roll history.

Bayard Rustin

When you think of the Civil Rights Movement, there is one person missing: Bayard Rustin. Despite not being as talked about as his contemporaries, Rustin was a key player behind the scenes. He was one of the key organizers of the March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom in 1963, even though most people only associate the march with Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Bayard Rustin was a huge influence and tireless fighter for civil rights dating back to the 1940s. So, why wasn’t he more prominently featured and why don’t we talk about him much? Several reasons — his ties to communism and his increasingly centrist political viewpoints are factors, but the biggest reason was because Bayard Rustin was gay. Remember, this was the 1960s. Being black was bad, but being gay was even worse.

He had initially kept his sexuality secret for personal reasons, but was outed in 1953 after being arrested for having sex with another man in a car in Pasadena, CA. Sodomy was still illegal back then, and he served 60 days in jail. So his record would come up every time someone tried to put him at the forefront of the movement. He began to speak more on gay rights in the 1980s, towards the end of his life. In 2013, Bayard Rustin was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama. Rustin died in 1987.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos

While you may not know Tommie Smith and John Carlos by name, chances are you have seen the famous photo of them holding their fists in the air from the 1968 Summer Olympics. After Smith won the gold medal and Carlos the bronze in the 200 meter track and field event, they brought their protest against the way black Americans were treated in the U.S. to the medal podium. They both wanted to wear a full pair of gloves but ended up splitting a pair. Additionally, neither wore shoes, their feet clad in black socks to represent black American poverty. During the national anthem, they both raised their gloved fists in the air in the “Black Power” salute. They also wore button for the Olympic Project for Human Rights, as did the silver medal winner, a white Australian named Peter Norman.

After it was decided that their political move was against the spirit of the Olympic games, Smith and Carlos were forced to leave the Olympic games. The act had negative lasting effects on both of their lives and careers, but that moment will go down as one of the most visible moments in black history.

Again, this is just a taste of all the people who have moved black history in this country forward. There are literally thousands more to include in the list. But remember, black history is American history, and we don’t just have to celebrate that in February.

This article was originally published on