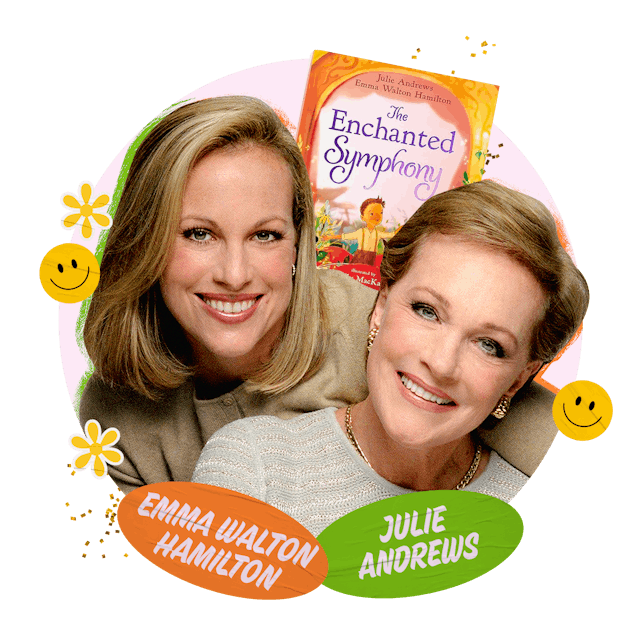

Julie Andrews & Her Daughter Wrote The Sweetest Children's Book

The beloved actor and her daughter, Emma Walton Hamilton, talk to Scary Mommy about their 27-year long writing partnership and what inspired their latest book, 'The Enchanted Symphony.”

Can childhood even exist without Julie Andrews? It’s unclear. But it is clear that the beloved Mary Poppins and Sound of Music icon seems to have some deep almost mystical understanding about creating meaningful art for children — and she hasn’t stopped making it for some seven decades. Not only that, but her daughter, Emma Walton Hamilton, seems to have the same special magic.

Together the pair have published over 30 children’s books over the past 27 or so years, beginning shortly after the birth of Walton Hamilton’s son. These books are truly made with kids in mind, and many, like the Dumpy the Dump Truck and The Very Fairy Princess series, have become classics in their own right.

Their latest effort, The Enchanted Symphony, has all of the charm of the duo’s earlier work, with a focus on the interconnected importance of music, art, and nature. It’s about a little boy named Piccolino who lives in a small town that’s overtaken by a strange fog when the townspeople get distracted and lose interest in simple things. But the boy saves the day when he realizes that returning to the small joys of art and music can eliminate the fog and revive the town.

Andrews and Hamilton sat down to talk to Scary Mommy about the COVID-related inspiration for the tale, how their mother-daughter relationship turned into a writing partnership, and exactly how they go about creating such magical stories for children.

Scary Mommy: I read that The Enchanted Symphony was inspired by an event you saw during COVID.

Julie Andrews: Have you seen that wonderful photograph that we refer to in that back page? The tribute to the original inspiration for the book? It's this entire little opera house in Barcelona just filled with green plants. And it was during COVID... and so this rather inspired gentleman, a wonderful artist, decided to just fill it with plants and houseplants. He got anything he could from anybody, and then invited the quartet of the symphony that played at the opera house for the plants.

And there's a little video of it, isn't there? And you swear that the plants are maybe just trembling a little bit. And it's possible that the plants are very much aided by or they love to hear music, if you are careful enough and watch enough.

The big challenge for Emma and for me was how do we not talk about COVID? We didn't want to bring the pandemic into it. The picture that we saw was all about the pandemic and the plants were there because of it. But what could we come up with that might invite a number of plants into the Opera House?

Emma Walton Hamilton: Mom had originally found that image and she was very excited by it and shared it with me. It so captured our imagination because it fuses together two of the things that we are most passionate about in the world, which is the arts and nature. And so when we were trying to brainstorm what the story might be about, we came up with this idea of a mysterious fog that blankets the village.

Not so much as a metaphor for COVID, although it could certainly be that, but more as a metaphor for or any of the distractions in life that can pull us away from remembering the things that we value most. It's a fable. How could we make it happen in a way that feels timeless and not necessarily connected to any particular specific place or time, not Barcelona, not the pandemic. And then we found our wonderful, wonderful illustrator, Ellie MacKay, and we were delighted when she said she'd agreed to illustrate it for us. We had serendipity all the way.

SM: Tell me more about what you think the connection between art and nature is.

EWH: Divine inspiration. I think one of the happy things that we often find when we are lost in creativity of any kind is that it often feels like it comes from somewhere outside of us — we go back and look at it and say, who wrote that? Where did that come from?

JA: We're both passionate lovers of nature and our gardens and countryside and walks.

EWH: Nature reminds us to us that there are forces out there that are bigger and more important than we are. And I think art does the same thing. Noticing the wonders of those gifts of nature or the arts for us — those are the values that matter most. That's what we were trying to say. And we ask that eventually of the child or the reader that's reading the book: What matters most to you? What's valuable? Forget about commercialism and all of those things. It’s about the mindfulness that it takes to keep those things front and center.

SM: You both have such varied careers. Why children's books in this era of your lives?

EWH: Children's publishing is very nurturing. It's very mission-oriented because of course we're writing for children and you better do it as well as you can. It's an awesome responsibility to get it right.

But there's also wonderful challenges inherent in writing for young people. There are certain rules that you have to write within. There are limitations on word count and on page number and on not writing what the art will show. All of that is a really challenging and fun puzzle. In the end, because we love children.

JA: And we love words.

EWH: And we love words. And we're both keenly aware of the degree to which the right book at the right moment changed and impacted our lives — and to hope that maybe one day, perhaps something we wrote might fall into the right hands at the right time of a young person in development. I think would be the greatest gift of all.

SM: What books did you read as children that changed your lives?

JA: I loved many books when I was a child, and that’s the same for Emma, but one particularly stands out and has probably influenced my writing. It was a book in England called The Little Grey Men. It's a nature study, much like Watership Down or Wind of the Willows, but it's about the last four gnomes living in England. They're very ancient but very active, and they are nature people and they live on the edge of a brook. It's an enchanting book, which sparks your imagination.

EWH: The book that really influenced me the most was Norton Juster's The Phantom Toll Booth. That was the book that made me fall in love with language. And because of the scene where they're in the open air market and selling and buying and trading words and letters — and words have color and taste and texture and aroma, it just completely opened my mind to the concept of language as being sensory and having so much dimension.

SM: How did your partnership begin?

JA: My publishers asked me if I had anything for very young children, maybe boys in particular, because that was harder. So I came home and Emma had her one-year-old son, and I said, if you're going to the library for Sam, what would you want to get for him? And she said, ‘Oh mom, there's absolutely no contest.’ It would be about trucks because he was truck crazy.

EWH: He was a total truck fanatic sheets with trucks, shirts with trucks, videos of trucks, pajamas. That was his whole world and nothing else. And I was night after night reading the same thing — ‘You Can Name 1000 Trucks!’ — to him every night. And I was desperate for something that had a little bit more substance. So mom said, well, maybe we should try writing it together.

JA: It was a total experiment and it happened and it became our series for young children called Dumpy the Dump Truck. And there were eight books. And of course the great good fortune was that Emma's dad and my first husband was a phenomenal artist, illustrator, set designer, film designer, costume designer. And he did the most beautiful illustrations.

SM: I trying to imagine working so closely with my mother on an artistic project. How does that partnership work? Do you get along? Is it bolstering?

EWH: It is bolstering — and that was a happy surprise. We weren't sure whether we would be compatible. We had both worked together creatively in other arenas prior to writing together in the arts. So we knew that we had a common creative language and love of the arts and literature.

But what we discovered working together was that we have different strengths, which happily are compatible with one another. I tend to be more about the structure and the nuts and bolts and the first act, second act, third act thing — I teach creative writing at the university level.

Mom is the one who comes up with the great opening line, closing line, interesting character details or images, things like that.

JA: Or turning left all of a sudden into a sudden surprise.

EWH: We never had a formal conversation about this, but we seemed to both intuit that the best idea wins. And so whenever we are inclined to disagree about something, which isn't that often, then each of us speaks passionately to it.

JA: We're not similar. We really are somewhat different. And we do sometimes have different opinions —

EHW: Or hassle over a word or something that —

JA: Or change in this or concept —

EHW: But we know the best idea —

JA: — When we hear it. As you can see, we finish each other's sentences.

SM: I've noticed that a lot today and it's adorable.

EHW: And that's how we write. We outline and then we literally we write the story out loud and finish each other's sentences. And I type as we go.

JA: And then it's endless revisions, as you can imagine.

EHW: One of the things that we didn't expect, and that has been a nice bonus, is that when we're working together creatively, there isn't time or room for some of the other family frictions that might get in the way and affect our relationship. We can't take up too much time complaining about other family members or politics or aches and pains or whatever it might be, or bickering. There isn't time. We got to stay focused on the creative problem we're trying to solve.

JA: We actually forget about them. That's the pleasure.

EHW: And that means that a lot of our time together is spent creative problem solving, which has turned out to be a really good thing for our relationship.

JA: It's actually terrible corny thing to say, but it's sort of like a small vacation or break an island in the day or something.

SM: Emma, you wrote a book about raising bookworms. Give us your best advice for parents who want their kids to love reading.

EHW: I did write that book largely because I was keenly aware of the degree to which the explosion of the digital world was pulling my kids as well as anybody else's. And so I did a tremendous amount of research. And what it seems makes the single biggest difference in terms of whether you raise a child who loves reading or not, is letting them take the lead in terms of what they read, how they read, how and where they read it, and letting them follow their passion, making sure that it always stays a pleasure and doesn't get associated with chore or punishment or homework or responsibility. So it's so easy when in the beginning when we're reading to kids picture books and they're on our laps and we're snuggling and they're getting this message that reading equals love and nurturing and all of that.

And then they go to school and they start learning to read independently. And often parents pull back from reading to them at that point thinking they need to encourage the child's independent reading. All of a sudden, instead of reading equals love, reading now equals chore and reading equals hardship and frustration. And so it's terribly important to continue to look for ways to connect reading with love and joy and pleasure and to raise bookworms.

SM: Julie, you have a lifetime of creating these really magical pieces of art for children. What do you think is most important about connecting with children in such a timeless way?

JA: A lovely question. It was something that I eventually learned was happening, and I was fortunate enough to be the conveyor of some lovely stories. And I'm talking about the films and theater and so on, and I've been raised in it my entire life. My parents were also theater people, albeit very different.

But for me, I became aware of how thrilling it was when children identified with something or wanted more of something. And actually in general, I became aware of what it's like to give. And it took me many years of doing because my family needed money and because it was an obligation and so on, to begin to realize that I could also give great pleasure.

I'm not saying that the films didn't give pleasure, but my thought process eventually became: I can give you the best evening I hope that you've ever had. Or I can sing this song that has got the most beautiful words. That certainly influencing some of our books because it is the same thing. You are dealing with words and conveying a story. And I think it was a natural evolution for me learning about myself.

SM: What is your best piece of parenting advice?

EWH: I know what [Julie Andrews] taught me when my kids were little and things got hard. Mom would say to me, just watch. Just when you think it can't possibly get any harder, just when you think you can't take it anymore. Whatever tricky phase they might be in, it will shift and it will change. And they're in the next new phase and they're onto the next thing.

JA: Keep your promises. I think it's terribly important to keep your promises for children, so many separated parents and things like that, have a hard time doing that. And if you say you're going to pick them up at a certain time or you're going to get 'em a certain thing or you're going to do something, keep that promise because it matters so much.

EWH: It also matters so much to let them lead. Children are not here to be molded by us into little versions of ourselves. They are individual human beings. Allow them the freedom to find who they are and let them lead the way in expressing that and support them in expressing that.

JA: One of the best things I was ever told was, when in doubt stand still. If everything around you is in a terrible panic and you are also in a terrible panic, then it's like a moth at a flame or a lamp, and you have to wait until that moth will calm down. The best solutions will happen if you give it a little time.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

This article was originally published on