The Girl Scouts Are Pissed About Flint's Water Crisis And You Should Be, Too

These Girl Scouts want Michigan Governor Rick Snyder to work harder to fix Flint’s water crisis.

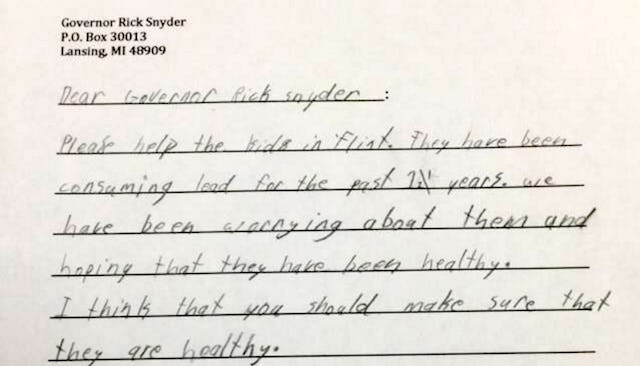

We’ve all watched in horror as the Flint, Michigan, water crisis unfolds, but a troop of Girl Scouts decided to make their voices heard. Brownie Girl Scout Troop 71729 has been writing letters to Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, asking him to help the people of Flint — especially little kids like them.

The letters were shared by independent citizen science organization Flint Water Study, who’ve been working to bring people up to date information on the crisis. In case you need a refresher, President Obama declared a state of emergency in Flint on Saturday after a 2014 switch to the Flint River as the city’s main water source led to corroded pipes and unknown number of people were poisoned by lead. We’ve all been stewing in our collective outrage, but somehow these Girl Scouts found a way to express it the most frank and heartbreaking way possible.

“I’m so mad,” one wrote. “Flint’s water is not good for kids to drink and eat. It is lead.”

Said another, “Please help the kids in Flint. They have been consuming lead for the past one and a half years. We have been worrying about them and hoping that they have been healthy. I think that you should make sure they are healthy.”

Another wrote, “We are worried about the kids in Flint. That can make them sick!”

One even tried to kill him with kindness, writing, “The kids in Flint do not have clean water and the water might have lead in it. And the kids are consuming it. I would like you to fix the lead pipes and make sure they have what they need. I hope you like this idea. Thank you.”

According to CNN, the decision to switch the city’s water source to the Flint river was a cost-saving measure, and officials knew the water was of poor quality. A 2011 study found the water could be potable if treated with an anti-corrosion agent that would cost about $100 per day. The water was never treated and people began to complain of water that looked, smelled, and tasted off, but were reassured over and over again that everything was fine.

Meanwhile, a local doctor named Mona Hanna-Attisha was seeing a steady uptick in cases of children with severe rashes and hair loss. Medicare requires states to keep records of blood lead levels in toddlers, so she compared current levels with past levels and found, to her horror, that in some children the amount of lead in their blood had doubled or even tripled over a two-year-period. Children are most susceptible to lead poisoning, which can result in poor fine motor skills, speech impairments, and even brain damage.

The water supply in Flint was switched back to Lake Huron in October, but the damage has been done: every single one of Flint’s 8,657 kids under six years old is considered exposed to toxic amounts of lead. Governor Rick Snyder has vowed to do “everything in his power” to solve the crisis of lead contamination in the city’s water and asked legislators for $28 million to fund immediate action; however, Flint Mayor Karen Weaver has said the costs to undo the damage caused by the toxic water could be anywhere from $1 billion to $1.5 billion.

The frustration and heartbreak these Girl Scouts expressed in their letters to Governor Snyder say, in such simple words, how every single one of us is feeling. We’re angry and we’re devastated that something like this could happen, and we’re infuriated on behalf of every adult and every child who will suffer lifelong health problems because of a massive failure by the very officials they elected to represent their best interests. There’s no way to fully undo the damage that has been done, but as these innocent Girl Scout letters prove, there’s nothing more important than doing everything we can to help the people of Flint.

You can help out by donating to the Flint Child Health and Development Fund, the Flint Water Fund, or the Flint Water Study.

This article was originally published on