The Electoral College Is Not Necessary—Let's Address The Common Concerns

By now, most people know that the offices of president and vice president are decided not by popular vote, but by a system called the Electoral College. Unlike other U.S. political races that are decided by popular vote, this “winner takes all system” of electing a president means that states essentially hold their own elections for president, and no matter how narrow the outcome, all of a state’s electoral votes go to the candidate who won that state. Even if a state is split 50.1% by 49.9%, 100% of the electoral votes of that state go to the candidate with the .2% margin lead. In other words, the votes of the 49.9% are not only nulled, but are changed to the other candidate. This is the Electoral College.

A Brief History Of The Electoral College

The Electoral College is one of the most famous “compromises” in U.S. history. It was formed by the Constitutional Convention of 1787 by the founding fathers as they attempted to devise a method by which to select a president that would separate the office of the presidency from Congress and thereby protect the office from political corruption.

Popular democracy was a new idea at the time. Allowing potentially uneducated and ignorant citizens the power to choose who governed them struck many as shocking. Some of the original framers believed the president should be elected by Congress, by state governors, or by state legislatures—that citizens shouldn’t vote directly for the president at all. Others were in favor of direct popular election. The Electoral College was the compromise.

As part of this compromise, since southern slaveholding states felt their less populous status put them at an unfair disadvantage, they negotiated that their slaves be factored in to determine the number of electoral votes their states would contribute. Drafters agreed that an enslaved person would be counted at a rate of 3/5ths of a free person, thereby increasing representation of slaveholding states and making it more “fair.” In exchange, the 3/5ths count also figured into the amount of tax these states would be required to pay to the U.S. government.

Aside from the 3/5ths compromise, the Electoral College remains in place with little change. But do we need it? Does it protect us from some nefarious outcome? Supposedly there are good reasons to keep the Electoral College in place. Let’s address the most common of these.

Without The Electoral College, Presidential Candidates Wouldn’t Campaign In States With Small Populations

This is one of the top reasons people bring up for why we should keep the Electoral College. Without it, proponents say, presidential candidates would have little reason to campaign or give any attention anywhere but populous cities. Rural areas would be left out.

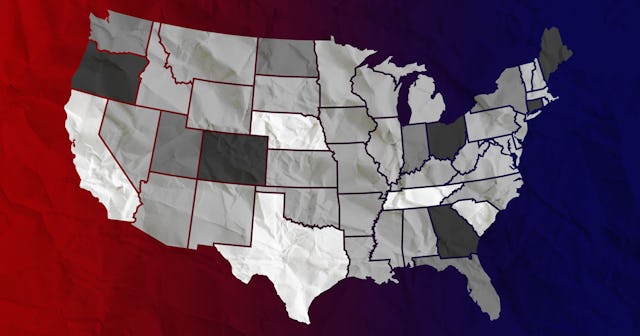

The problem with this argument is that presidential candidates already don’t campaign in places where they perceive no strategic benefit. Both parties avoid campaigning in states that traditionally lean red or blue and instead focus their efforts entirely in the 12 swing states. Even within that small portion of the country, candidates’ advisors analyze polls and determine which of those swing states need the most attention. In other words, 38 states out of 50 are currently overlooked by presidential campaigns.

Moreover, with the advent of the internet and the ability of candidates to reach voters digitally, the idea of campaigning in person is moot. If a voter needs to attend a rally in order to educate themselves about a candidate’s policy, that voter has larger issues than simply feeling neglected by their party. Candidate rallies are just that — rallies — to excite an already loyal base. They are not educational; they’re tools to pander.

Without The Electoral College, Less Populous States Wouldn’t Have Fair Representation In Government

Element5 Digital/Unsplash

“This isn’t the United States of California and New York,” people say. It isn’t fair for populous areas on the coast to decide on behalf of the rural middle.

Here it is necessary to address people’s understanding of how our government works. The United States is not a pure democracy. It’s a republic—a country composed of individual states. Each state is represented in an equal sense and in a proportionate sense in the U.S. congress, which passes laws. Congress is made up of the senate and the house of representatives: 2 senators per state (equal representation), and a number of representatives determined by population (proportional representation).

In other words, when it comes to equitably distributing representation in terms of policy and lawmaking, the structure of our government already has that covered. Every state already has state-based “all or nothing” representation based on popular votes in their state in both the house and the senate.

The president, on the other hand, does not pass laws, declare war, print money, regulate commerce, or control immigration. The president does not represent any individual state—he or she represents the country as a whole. Therefore, every vote for the president should carry exactly equal weight. The only way to achieve that is by popular vote.

Taking all of this into consideration, the argument that abolishing the Electoral College would mean citizens in less populous areas would lose representation is simply false. The drafters of the constitution set up this system of checks and balances with the intent that each state is represented equally and proportionally by congress, and that the people decide the president. In fact, the original drafting of the Electoral College did not instruct states to apportion all electoral votes per state to the winning candidate in that state.

States could, and still can, opt to apportion their votes based on a ratio of candidates’ support. Nebraska and Maine each apportion their electoral votes based on congressional districts, for example, dividing their votes between the candidates based roughly on what the citizens of that state actually choose.

But Isn’t It Still Really Unfair For Densely Populated Coastal Cities To Decide Who Is President?

The reasons above should be adequate, but let’s go ahead and address this question in another way. The claim is, at its core, that abolishing the electoral college would disenfranchise certain voters.

Except, we already have mass disenfranchisement as a direct result of the Electoral College. Everyone who lives in one of the 38 states that isn’t a swing state and votes against the majority of their state is disenfranchised. If you’re a Republican living in a blue state, your vote for president is essentially irrelevant. If you’re Republican living in a red state, even then your vote still doesn’t count for much since you could reasonably sit out an election without affecting the result.

We have set ourselves up with a situation in which millions and millions of votes hold no weight at all. Worse than that, their votes are switched to the opposition party. Almost half of Florida voted for Biden, and yet Trump got all 29 of our electoral votes. So, the argument that it “isn’t fair” for coastal cities to decide who is president simply doesn’t hold water. The only way for every vote to have equal weight is to actually give every vote equal weight.

The Electoral College Discourages Voter Turnout

The United States has some of the lowest voter turnout of developed democracies. Is it any wonder? When one can easily justify that their vote for president is irrelevant based on their geographical location, why should they show up to the polls? Unless you live in one of the 12 swing states, it is reasonable to conclude your vote doesn’t really matter.

Moreover, the Electoral College perpetuates disenfranchisement. In his book, Let the People Pick the President, Jesse Wegman, a member of the New York Times editorial board, points out that since the number of electors in a state is based on total population and not registered voters or actual voters, there is no incentive for states to encourage citizens in marginalized, minority, or otherwise disenfranchised groups to vote.

We saw in Georgia what can happen when disenfranchised people are mobilized. Voting rights activist Stacey Abrams registered more than 800,000 new voters, a move that turned Georgia, historically usually a red state, blue. Without that massive effort, in a state assumed to go red in 2020, many of those voters may not have bothered.

Why Don’t States Do A Proportional Allotment Of Their Electoral Votes, Like Nebraska And Maine?

There are two arguments against proportional allotment. The first is that gerrymandering would become an issue. Just as gerrymandering occurs now to draw districts boundaries to favor either party in the house of representatives and state legislative bodies, the same thing would happen when trying to draw districts in an attempt to apportion electoral votes.

The second argument is a problem of each state having adequate electoral votes to accommodate such apportionment, especially in an election where a third party is trying to gain a foothold. Texas, with its 38 electoral votes, could easily divide its electoral votes according to the support of each candidate, even if there were more than two candidates. States with 3 or 4 electoral votes would have a harder time giving weight to a third party. As much as Americans claim to be sick of the two-party system, the Electoral College perpetuates it. Consider this: A third party candidate would have to win over 50% of votes in at least one state to even make it on the map. Under our current system, that is all but impossible.

But Doesn’t The Electoral College Prevent Runaway Elections Of Highly Unqualified But Charismatic Leaders?

If anything, it encourages it. As the past four years have shown, the Electoral College is just as susceptible to manipulation as a “one person, one vote” system might be. But, again, the drafters of the constitution considered this potential abuse of power. It’s why they created a multi-branch system of government that separates executive, legislative, and judicial power.

What Are Our Alternatives?

Ranked choice voting (RCV) comes up a lot. With RCV, voters rank multiple candidates by preference rather than vote for only one. If there is no clear winner in the first count, a second round tabulates voters’ second choice and adds that to the original total until one candidate has more than 50% of the votes.

RCV could potentially break up the two-party system currently exhausting so many Americans, allowing burgeoning parties to have a seat at the table. It could enable candidates to run based on policy rather than partisanship. Voters, having more than one option, could vote for their first, second, and third favorites. Instead of voting strategically for the “lesser of two evils,” they could vote for the candidate whose policies align best with their values. They could have a favorite, a second favorite, and be mostly satisfied if either won.

Another movement currently underway, the “National Popular Vote Interstate Compact” (NPV), is an agreement among participating states to award the candidate with the most popular votes their electoral votes, regardless of which candidate won in their state. The purpose of this is to circumvent the required constitutional amendment that would be necessary to abolish the Electoral College, an event that is extremely unlikely. 16 jurisdictions comprising 196 electoral votes have already agreed to participate. In order to pass the bill, they would need enough states to join the compact to accumulate 74 additional electoral votes. According to the NPV website, “a total of 3,408 state legislators from all 50 states have endorsed it.”

Regardless of the path we choose forward, we need to reexamine the usefulness of the Electoral College. When a candidate can win the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes and still lose via the electoral college, when a candidate can win the popular vote by over 4 million votes and the election is still “close,” that should be a conspicuous signal to us that our system is in need of revision.

This article was originally published on