The Greatest Lesson My Father Taught Me

This is what I remember:

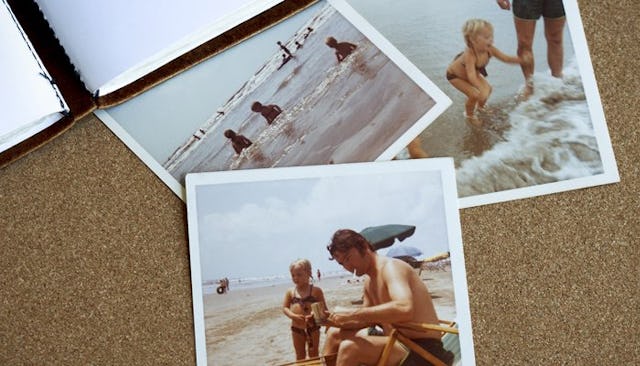

My dad would rise early and take the train from the suburbs to the Loop in downtown Chicago. He’d work all day in a tall office building on Jackson Boulevard that I saw only once, on a special Saturday he brought me with him, a day I remember by the greenish glass of the train windows and the overflowing ashtrays and stacks of papers on brown desks, and by the way my ears popped as we rode the elevator to the top of the Sears Tower at lunch.

He’d come home on the same 5 o’clock train every night. When the front door opened, I’d run from the family room, through the kitchen, into the dining room, and around to the foyer to surprise him. I’d hug him, my cheek resting against his trench coat that smelled of cold and smoke and train exhaust.

He’d disappear down into the basement and I’d hear the thump thumping of the punching bag. I’d watch him take a long drink at the kitchen sink, sweat dripping from his chin. Later, I’d rest in the crook of his arm, his deep, smoky voice vibrating through his chest and into my ear as he read me a story.

This was his life as I saw it. Routine. Secure. Happy. It wasn’t until I was older that I found out he woke up every day to a job he hated.

I don’t know if he said it to me only once or a thousand times. I don’t remember how I first learned it. Whatever the case, I can see him now, shaking his head, his blue eyes sad, “Don’t ever take a job you don’t like. It’s not worth it. Do what you love.”

When my dad was a child, he loved reading. He read Treasure Island and The Ted Williams Story and Crime and Punishment and comic books. He read in his bedroom, to avoid being teased by the neighborhood kids. He read everything.

This is how I’ve known him, too. He loves a good story in all forms—books, movies, TV, music. Conversations with my dad were my first lessons in story: how to put one together, what is compelling, how to think about the arc, dialogue, setting. I remember his delight at the repetitive talk of weather in the movie, “Fargo”—that this dialogue showed not just an interest in weather, but a universal human desire to connect without having anything to say.

When he was in college, my dad thought about majoring in literature and becoming an English teacher. Someone—a well-meaning college counselor, perhaps—told my dad, “You’re good at math. Go into accounting. You’ll always have a job.”

He took that advice and as things go, he became an accountant. He got married and had a family that depended on him. He was sad, I know, not to be doing what he loved. But my dad didn’t sacrifice himself for us on purpose. If he’d had a looking glass, and saw the years of numbers and tax documents stretched ahead of him, he wouldn’t have become an accountant. He probably would have run straight to World Literature class.

But in a way, he did sacrifice. Because it’s the mistakes of our parents that serve as some of our strongest lessons. We learn from them and, hopefully, become better, happier. It’s our responsibility to do that. Otherwise, what’s it all for?

And so I’ve followed my own path and my own heart, and I’ve never, ever considered taking a job I’d hate. I’ve worked as a reporter, a political communications director, and an author. I am guided by my love of writing and storytelling. I am guided by a true sense of what’s important, of how short life is and how responsible we are for making ourselves happy. My father gave me that.

I’m a parent now. I will make mistakes, and my children will learn. I will make sure of it, as my father made sure for me.

They will know from my mistakes, but they will also know the greatest lesson I can teach them. Because I remember, will always remember, my father’s words: Do what you love.

His grandchildren and great-grandchildren will know those words, too.

This article was originally published on