This Is What I Learned After Almost Losing My Daughter

“Mama! Mama!” My 1-year-old daughter cried over the baby monitor.

“Coming,” I responded, setting my fresh coffee on the table.

I strolled over to her bedroom door, the words “Good morning!” poised on my lips. But when I entered her room, I noticed she wasn’t standing up, as she usually did, waiting to greet me with outstretched arms. Instead she was sitting down, partially hidden behind the rail of her crib.

And then I saw her.

My daughter sat motionless on her bed covered in a thick blanket of blood. A stream ran from her nose onto her pajamas and skin. It caked her blonde hair, making it appear black and clumpy. When I reached for her, her head flopped to one side like a rag doll.

“Something’s wrong with the baby!” I screamed to my husband who slept in the next room.

Moments later, he ran panicked into the nursery. The look of horror on his face when he saw her mirrored my own. He tipped her head back and pinched the bridge of her nose, attempting to staunch the flow of blood, but it continued to pour from her nostrils, unabated.

“We need to get her to the ER,” my husband urged, pulling our daughter’s blood-soaked blanket protectively around her.

I took a deep breath and nodded, following him to the car. Through my shirt, I could feel her heart racing against my body, a thrum-thrum-thrum that filled the silence all the way to the hospital.

Once we arrived, we were ushered into a private room where we waited for the attending physician. He arrived moments later with his assistant in tow, both appearing visibly shaken by the appearance of our daughter. Every part of her body — and mine — was bathed in various shades of red. After a brief examination, we were told she needed immediate transfer to Texas Children’s Hospital.

Inside the ambulance, I scanned the length of my daughter’s body with breathless anxiety, trying to reassure myself that her chest was rising and falling. I clutched her unresponsive hand in mine and told her how afraid I was.

And then suddenly her body heaved and a torrent of bloody vomit poured from her mouth. It felt like a million tiny, invisible threads twisted tightly around my throat all at once, yanking the air out of my lungs. I couldn’t think. I couldn’t move. I could only emit one unearthly scream after another.

When we arrived at the hospital, 30 minutes later, dozens of men and women donning white lab coats surrounded her, hooking her up to medical machines and tubes. A cacophony of high-pitched voices ricocheted around the room.

My husband and I stood off to the side, terrified and dumbstruck, willing her to stay strong.

“Hello, Sir/Ma’am?” a woman said, startling us. “Please come with me.”

Silently, we followed her to the back of the ICU.

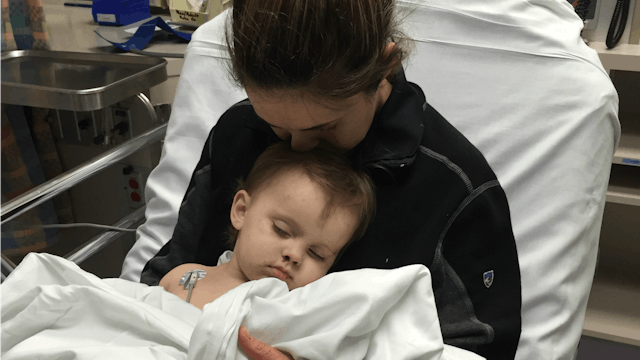

Lauren Lodder

The doctors at Texas Children’s discovered that our daughter’s platelet count was dangerously low. To put it into perspective, a normal platelet count for a child is between 150,000 and 300,000. Our daughter’s platelet count, however, was 3,000. This is problematic, of course, because the lower the number of platelets, the higher the risk a person has of hemorrhaging because his or her blood isn’t able to clot normally.

When our daughter developed a nosebleed, her platelets should have stuck together to form a kind of seal over her wound. But this didn’t happen. As a result, she suffered significant blood loss, developed anemia, and required a blood transfusion. Our daughter — who just yesterday appeared to be perfectly healthy — was now having an IV line inserted into her vein so donor blood could save her life.

Over the next several hours, doctors of various specialties visited our hospital room, checking our daughter’s vitals and reassuring us she was doing well, all things considered. They used words like leukemia and thrombocytopenia (ITP), and told us more tests were needed before they had answers.

“What’s happening now?” I’d ask our doctor every few minutes.

“We will have answers soon,” she’d respond.

Early the next morning, we learned our daughter did not have blood cancer, but she did have a blood condition called idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Her doctor suspected that at some point in the previous month our daughter had developed a viral infection and her immune system responded by attacking not only the virus but also the platelets in her blood.

The appropriate treatment was called intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusion therapy. The therapy was intended to reboot her immune system so her body would stop attacking itself.

And thank God, that’s exactly what it did. Twenty-four hours later, her platelets had returned to a normal level of 150,000, and 24 hours after that we were able to take her home.

One year has passed since our daughter developed ITP. We still have no idea what caused her condition. But here is what we do know: Roughly 4 out of 100,000 children develop ITP annually; symptoms range from petechiae and excessive bruising to severe bleeding and sometimes death. For most children, it does not become a chronic condition. And fortunately it didn’t for our daughter.

However, that does not mean it didn’t have a lasting impact.

Our daughter’s hospital stay taught me that terrible, unexpected tragedies can happen at any time, to anyone, and there is nothing I can do to prevent that from happening.

But what I have learned over the past year is I cannot live my life in a constant state of worry. I can’t visit the doctor every time my child develops a bruise because I’m afraid the ITP has returned. I can’t allow the emotional trauma of the incident to cast a dark shadow across my life, and more importantly, across her life. No, absolutely not.

What I can do, however, is focus less on all of the terrible things that could happen to my child and turn my attention to all of the great things that are happening to my child. For example, I can celebrate the fact I was able to take her home. I can be grateful she is here today because of the doctors who worked around the clock to keep her alive.

That’s what I can do, and that’s what I am doing.

Because being a parent means putting your own worry and fear and pain aside so you can be a comforting presence for your child.

I have to believe, for both of our sakes, that my child and I are going to be just fine.

Lauren Lodder