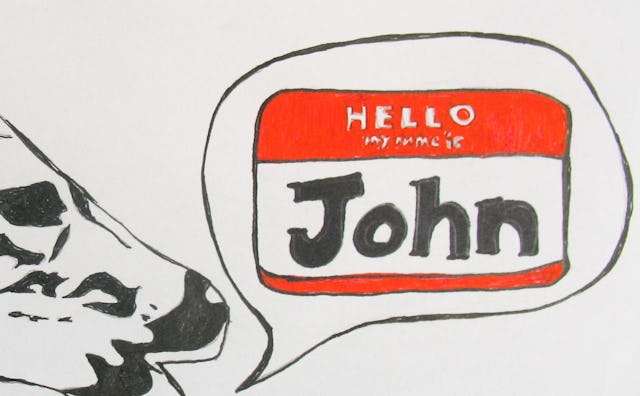

Why Immigrant Parents Shouldn't Name Their Kid "John"

My name is John.

A simple name, really. Right? Well, that’s not how it has worked out. For some reason, it surprises people that my name is not Jon, Juan, Jowan, Jaan, or Johan. While we’re at it, let me tell you what else my real name is not. it’s not Jonathan, Johnny (though I’ll take this one), or Jack. And it’s definitely not freakin’ JHON. When did that even become a possibility?! I doubt that any other “John” has had their name treated so woefully.

There’s this thing that happens when people see me. I admit, by growing this beard, I’m not making it easy on anyone. Certainly not the TSA folks that routinely pull me aside for “random” checks. (As you can imagine, I’m popular at airports). But it’s like people’s brains can’t interpret what they’re seeing and hearing. Everything’s in conflict. As I understand it, the way vision works is that we see whatever our brains think we should see. Apparently, a lot of brains are telling people: “There is no way this dude is named John. It’s probably Ali, or Samir. Maybe Gamal. Something ethnic. Anything else just wouldn’t make any sense. I’ve seen a guy like this before and his name was certainly not John.”

So when I tell you my name is, in fact, John, a lot of brains just can’t compute. They’re confused. There’s mayhem and sparking and overheating. The brains then summon their built-in “ethnic translators” to make sense of it all, and they start seeing “Jhon.”

What happens next? Simple – more questions. “How do you spell that?”

I always want to respond: “How the hell do you think it’s spelled?!” Or perhaps: “Um, like every other ‘John’ out there? (You bleeping-bleep.)” But I don’t. I spell it out. Does it end there? Never.

“Oh. Cool. But… that’s not your real name, right?”

Actually, it is. My parents – immigrants from Egypt – thought they were doing a good thing. Recognizing they were in a new country, they made the highly strategic decision to give me a name that sounded like I belonged. They didn’t want me to be made fun of as a kid. Growing up, I had a friend named Meena whose parents lacked the foresight that mine had. Or maybe they couldn’t fathom the notion that a name so popular in Egypt just wouldn’t work as well here. I’m not sure. Anyway, his childhood sucked. How could it not when you’re in the second grade and most of your classmates think you have an Indian girl’s name? Not to mention the nicknames – I’ll spare him and all “Meenas” out there (there are more than you think) the embarrassment here, but they’re not too hard to come up with.

Back to my parents. They came here to give their children opportunities that didn’t exist in Egypt. I was born here and am an American citizen, and they wanted to give me a name that matched – one that allowed me to fit in right away. Plus it was a name that everyone knew how to spell (Ha!). They envisioned their kids’ lives here in this shiny new country and didn’t want to risk a tongue twister of a name ruining their efforts.

My dad always made it a point to tell me I could be president of the United States. I would always laugh when he’d say it, and without fail, he would always respond the same way – “Why not? After all, you were born here, and you’re just like everyone else here.” Part of that I think, in his mind, was that my name was just “like everyone else’s.”

I picture the events that led to my naming going down like this: my dad is in a deep, satisfying sleep – the kind that transpires when things are going according to plan – dreaming about my future here in the U.S. He envisions me face to face with the Chief Justice, left hand on the Bible, right hand in the air. Then the anticipated announcement – “ladies and gentlemen, the president of the United States of America, Naser Gindy Malek Abuseif!” That moment in his dream must have just seemed a bit, well, off. He woke up in a panicked sweat screaming “John! We have to name him John!!” So despite being perceived as sell-outs by the brown community, my parents went with John. A name that would give me no trouble. Or so they thought.

None of this is their fault. They were doing what they thought was right. They couldn’t have foreseen that people would refuse to believe my name was what I was saying it was. And they stuck to their strategy. They named my two brothers Steve and Andrew. Oddly enough, they don’t get the same questions. Neither does my wife for that matter, whose name is Margaret and is also Egyptian. I wonder if it has to do with the fact that they look, well, less brown. (See pictures below.)

Maybe Meena’s parents weren’t so crazy after all. In the end, your name doesn’t change the way people see you, does it? Maybe I should change my name to something that most people expect. But could I ever become president with a name like Metthat, or Suleiman, or… Barack?

photo: flickr/Nick Richards

This article was originally published on