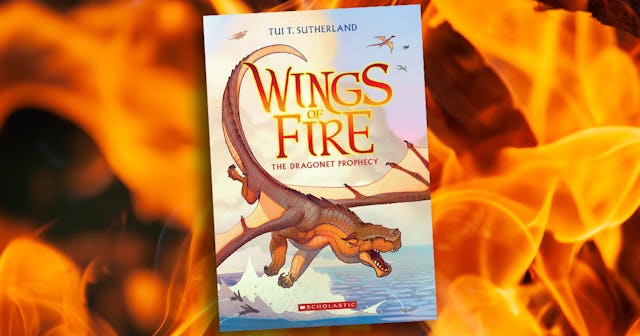

My Kids Begged Me To Read The 'Wings of Fire' Series With Them, And Now I'm A Superfan Too

For a solid year, my kids begged me to read Wings of Fire, a book series about dragons with which they’d become obsessed, and for that whole year, I brushed them off. They promised me I would love it. It sounded weird though — dragons who talk? A small band of misfit “dragonets” out to save the world? It sounded like any other kids’ book series, and it definitely didn’t fit my usual preferred adult-targeted genres.

But my kids wouldn’t stop pressing me to at least give the books a try. I’d never seen them so immersed in a book series. They were watching fan-made cartoons of the series on YouTube and filling their sketchbooks with their own personal visions of the various dragon characters. They were reading the books more than once and debating at the dinner table whether or not a character named “Darkstalker” was born a sociopath or made into one by a unique set of life experiences. And one day my daughter burst into my office to exclaim with glee that there were “gay dragons” in the story now.

Okay, fine. I finally agreed I’d at least give the first book a chance. I’d try to get to know the world of Pyrrhia and its dragon tribes a bit so I would have some idea about these supposedly “amazing” characters my kids could not stop yammering on about.

Welp.

Author Tui T. Sutherland had me hooked from book one, The Dragonet Prophecy — yes, “dragonet” means adolescent dragon. The book opens with a prophecy about 5 dragonets who are destined to finally end the war that has been raging through Pyrrhia for years. But these dragonets, hidden away in a secret cave for their own protection as they train for their great mission, are basically just a band of rag-tag misfits. None of them has any special powers or strengths that would lead anyone to believe they are capable of saving the world.

Tui T. Sutherland’s writing is energetic, heartfelt, and clever. She draws the reader to the center of the action without wasting words and without pandering to her younger audience with overly simplistic descriptions and dialogue. She writes the way I expect a writer of an adult-targeted thriller to write: with tension and forward motion in every scene. She shows and doesn’t tell. I think this is why so many adults end up getting sucked into the series right along with their kids. The writing really is that good.

Some parents have complained that the books are overly violent and graphic. The story is set in wartime, after all, and the dragons’ perception of “scavengers” (humans) is dismissive and violent. In one scene in book one, a villain dragon bites a human’s head off quite suddenly. Horrifying, and yet, in the context of the scene, it defined the careless apathy of the villain dragon.

I found Sutherland’s treatment of humans interesting because the dragons of Pyrrhia view humans much as we in the human-dominated world view rats or squirrels or any of our animal food sources — with arrogance. They flippantly wonder about the inner lives of “scavengers,” whether or not they have emotions or feel pain or care about things the way dragons do. This piece of the story provides an opportunity for readers to confront our own claims of being the most important animal on the planet, the only animal capable of complex feelings.

Sutherland subtly weaves this type of subtext — the kind that forces a reader to introspect and ask questions about what we perceive as morally obvious — throughout every book. For that reason, depending on how sensitive your child is, of course, I would urge parents to look past concerns of excessive violence in the series. To me, every violent scene is a lesson against violence, not a romanticization of it or an invitation to it.

The young dragons in these stories are called to a heroism beyond what any of them think possible of themselves. They balance standing up for themselves with looking out for others, and they are constantly learning and growing and trying to be the best dragons they can be. Sutherland approaches questions about democracy and personal freedom in a framework that feels like an adventure rather than a civics lesson. She uses story to address moral questions, like, “If you can read people’s minds, should you?”, “If you had the power to change someone’s feelings about something, would that be okay?”, and “Is it okay to lie to someone if you’re doing it for their own protection?”

At heart, every story is character-driven and highlights empathy, kindness, and inclusion. Each book is from the perspective of a different dragon, often from the perspective of a dragon that previous books portrayed as unlikeable. Because of this constant shift in perspective, readers get to see the history and inner thoughts of dragons that may have appeared one way on the outside, but once you read a story from their perspective, you realize that, just as with humans, there is always more to a dragon than meets the eye.

Sutherland’s treatment of an LGBTQ relationship is especially endearing — it’s completely seamless and ordinary. Many of the dragons have middle school-level appropriate crushes on one another, but those crushes are never the center of the story. Neither is the queer relationship when it comes up. There is literally no commentary on the fact that the two dragons who love each other happen to be the same gender, no questioning about the validity of the relationship from other dragons, no judgmental sideways glances, not even a discussion of identity. The relationship is simply addressed as two dragons who love one another.

So, my kids were right, big-time. Along with them, I’ve read all 13 books in the series so far, and the three of us eagerly await the next installment from Sutherland. I’m officially part of the fandom. And if you pick these books up for your kids, you just might get drawn into the fantastic world of Pyrrhia too.

This article was originally published on