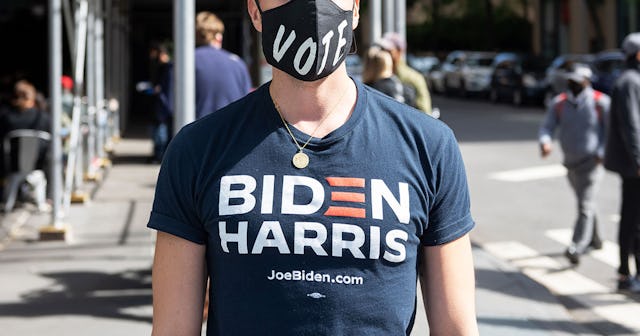

WTF Is Electioneering—And What Does It Have To Do With My T-Shirt?

You show up to your polling location totally jazzed, ready to vote for Biden (or against Trump; however you need to think about it, whatever, let’s get that human lizard out of the White House), and to show your enthusiasm, you wear your favorite Ruth Bader Ginsburg T-shirt—the one that says “dissent” under an image of her face—along with rainbow suspenders to show your support for the LGBTQIA+ community and a BLM pin to show your support for the Black community.

You literally could not be more jazzed, and you don’t care if your look is reminiscent of Jennifer Aniston in Office Space with her “flair.” It is time to do democracy, bitches!

Except, when you arrive to vote, poll workers inform you that you are in violation of a statute that prohibits the wearing of “political apparel” within one hundred feet of a polling location, and they ask you to either change your shirt or cover up. They tell you you’re “electioneering.”

Huh? Electcha-what? Electioneering is, basically, campaigning. On Election Day, electioneering is understood more broadly to mean “campaigning at a polling location.”

But it’s not like you’re wearing a Biden shirt (you don’t even have one) or your “dump Trump” shirt (it’s in the wash). None of the stuff you’re wearing is even on the ballot. Why can’t you show your support for BLM? And wait a minute—isn’t this a flagrant violation of the First Amendment’s protection of free speech? Polling locations are public property, aren’t they? How can they dictate what you wear?

SOPA Images/Getty

Well, they can, but only to a point, and they have to be specific about it. A 2018 Supreme Court ruling on electioneering established that a universal ban on political apparel does in fact violate the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. The case came about when a Minnesota voter was turned away from the polls for wearing a “Don’t Tread on Me” T-shirt with a Tea Party Patriots logo and a pin that said, “Please I.D. Me.” (Minnesota does not require I.D. to vote.)

But—and this is a pretty huge but—the ruling also clarified that states may restrict apparel as long as those restrictions are clear. The court’s main objection to Minnesota’s law in particular was that it was too broad and didn’t define the word “political.” The law left too much open to interpretation.

In the Supreme Court’s ruling, seven of the nine justices agreed that Minnesota was justified in prohibiting electioneering at polling locations in order to “set it aside as ‘an island of calm in which voters can peacefully contemplate their choices.’ … the State may reasonably decide that the interior of the polling place should reflect the distinction between voting and campaigning.”

In other words, because of the solemn nature of voting, for polling locations specifically, as with other specific cases, some restriction on speech is justified.

With that, much discretion is left to each state to decide how they will handle electioneering. Depending on the state you live in, and depending on how clear electioneering statutes are and how well (or badly) poll workers understand those statutes, showing up in politically charged garb could get you turned away from the polls or even land you with a misdemeanor.

In California, for example, the rules are strict about electioneering. Voters may not wear “campaign paraphernalia relating to any candidate, slate, or issue, including T-shirts, buttons, and stickers.” So, arguably, a Ruth Bader Ginsburg T-shirt could fall under that category. She herself may not be on the ballot, but the incumbent administration is currently reviewing a new conservative judge to fill her place, and that connection may be enough for a poll worker to determine you have crossed a line.

Bill Clark/Getty

All states have some kind of regulations pertaining to campaigning activities within a certain number of feet of a polling location. The rules in Florida, the state where I reside, are lax enough that I had never heard of electioneering until recently. There is nothing in the statutes about clothing, and Election Day campaigning is allowed but must be 150 feet from the polling location. Which explains the utter chaos I used to encounter every voting day before I switched to mail-in voting two years ago. But voter selfies or any kind of public display of your ballot are strictly prohibited.

Kansas may have the strictest electioneering laws, forbidding the “wearing, exhibiting or distributing labels, signs, poster, stickers or other materials that clearly identify a candidate in the election or clearly indicate support or opposition to a question submitted election within any polling place on election day…” and classifying such offenses as a class C misdemeanor, which could incur a month of jail time and up to a $500 fine. Delaware, Kansas, Montana, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Vermont are similarly strict in their restrictions.

So, before you show up in person, check your state’s rules on electioneering and plan your voting day outfit accordingly. Or, at the very least, bring a sweater, as most likely, if you are in violation of regulations, you will merely be asked to cover up. Voting truly is a sacred right, and whatever your feelings about your right to display your voting preference, this may not be the year to risk not having your vote counted—all the more so if you’re in a swing state. Happy voting!

This article was originally published on