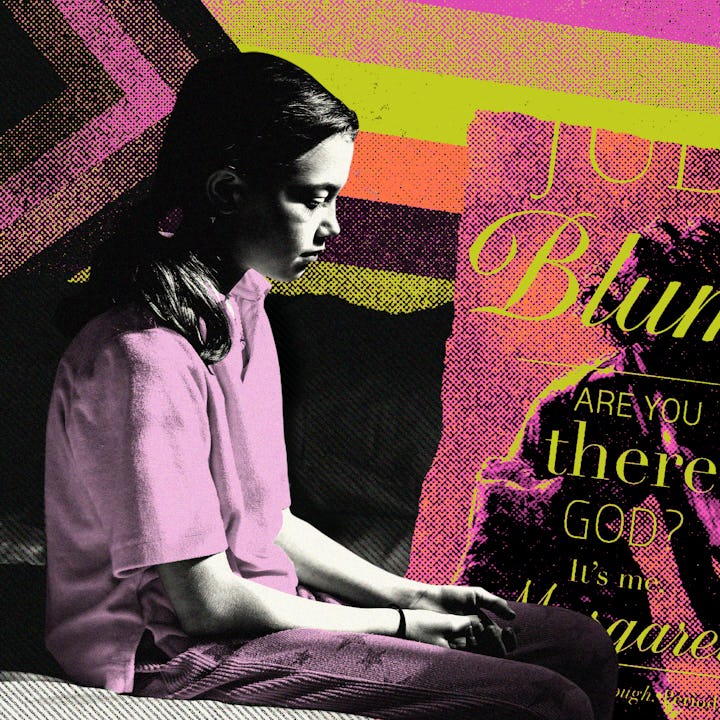

‘Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret' Is Iconic — But It’s Not Enough

Judy Blume's classic was important for many girls going through puberty. For me, it was a reminder that I wasn't comfortable with my gender.

I read Judy Bloom’s coming-of-age classic Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret when I was in middle school. I reread it a few months ago in anticipation of the movie’s spring release. Before re-reading it, I couldn’t remember many details or characters, but I remember the visceral feeling of not belonging. I was assigned female at birth and was seen as a girl, but Bloom’s book reminded me I didn’t feel comfortable being a girl and didn’t have any desire to be like Margaret or her friends. When I read the book again, that sensation came rushing back with renewed clarity.

In case it’s been a while: Margaret is an 11-year-old girl who has moved from New York City to the New Jersey suburbs. While making new friends and starting a new school, she comes face-to-face with puberty and is forced to look at her lack of connection to a specific religion. Her parents' marriage is an interfaith one — her mother is Christian, her father is Jewish — and she’s trying to figure out where she may fit in, if at all, with either or both.

Readers experience Margaret’s first crush, her desire for bigger breasts and her period, and her questioning of faith, topics that were considered taboo at the time, especially for females. Which is why the book was so important and resonated with so many people: Many girls finally got a chance to see themselves.

Puberty, religion, and growing up perceived as female are all themes I can relate to. But as a kid, the treatment of those subjects as a society, not just in the book made me feel different and inadequate — I didn’t fit the heteronormative mold that was the expectation regarding relationships and gender. Those expectations haven’t changed much, and I still don’t fit them. And there was another way my experiences diverged from those of Margaret’s: She was trying to find a connection to religion. I was born into a family of dogmatic born-again Christians. For me, much of adolescence involved trying to untangle my connection to religion, even if I didn’t know it then.

I was a tween in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. While my pegged pants and crimped hair were right on time, my feelings of attraction for girls were far from timely in the eyes of the church I was raised in. I understood the feelings of Margaret’s crush but not why my object of affection was a girl.

The church denounced homosexuality, and the fear of God and Hell was baked into weekly services and youth group meetings. If I was a Christian, then why wasn’t I good at it? I stayed deep in my closet of shame but believed God could still see me. People of faith told me he had eyes everywhere. I was taught that inviting Jesus Christ into my heart meant inviting the Lord into every piece of my life. Every piece? Yes. Oh God.

I took it to mean he could read my mind. If he felt the love in my heart for him, he must have known about the feeling I couldn’t describe when I was called a girl. If communion was taking in his body and blood, then he must have felt my fear and disgust when changes made my body more feminine.

I didn’t want to “increase my bust.” I was terrified of getting my period. And I certainly didn’t want a boy to notice me for any of it.

While I worried about God’s judgment, I also prayed for his help. Even then, it felt a bit like wishing on a star, because I wasn’t asking God to change me or make me “normal.” I just wanted him to keep my secrets. My conversations with God were much like Margaret’s: it was a confession, an unwritten diary entry I made when life felt confusing and out of control.

I didn’t recognize this then, but I was asking the dude who was supposed to send me to Hell for his allyship. And actually, I believe that, in part, got me through puberty. While friends were crushing on boys and learning about the dangers of white pants and wet shirts, I was looking for someone to tell me it was okay not to want to deal with any of it. And feeling like I had that direct line to somebody with whom I could be completely honest — because he already knew, after all — made a difference.

I learned in 5th grade that “only girls” menstruated and that it was a right of passage into womanhood. And because bleeding out of my body for several days a month wasn’t bad enough and what felt like the completely wrong path, my body could also grow a baby with the right ingredients. My religious mother introduced me to pads when I got my period and told me I was not to use tampons until I’d had sex with a man.

God? Are you there? This isn’t going to work.

And it didn’t — well, not the way it was “supposed” to.

****

Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret provided much needed representation for many young girls and women, but I could have used a book that talked about menstruation without gender. I would have benefited from a book that celebrated friendships with boys without the assumption of romantic affection. I needed, as do so many kids today, a book that described periods in biological ways only and without the implication of assumed relationships with gender and other people. My period got in the way of basketball practice; it didn’t make me a vessel to carry the seed of a man.

Puberty is weird and gross. First crushes are overwhelming and painful. Growing up is hard.

I didn’t come out as gay until 16, and as nonbinary til 38. God, it turns out, was never the problem or even the solution for me. The problem was the people who continue to this day to interpret the Bible to support their bigotry.

Thirty years of self-exploration and acceptance, therapy, and distance from toxic family members have given me peace and a healthier relationship with my body. I also have the knowledge to give my children, especially my 12-year-old daughter, the tools they need to develop healthy relationships with their own bodies. I want them to have a strong connection to their sexuality in ways that are both self-respecting and respectful of others. I have found resources in diverse and queer-inclusive sex ed books available today, but for the most part these conversations are still centered around cisgender and straight narratives.

I’m glad Judy Bloom pushed the conversation about puberty into the mainstream in the 70s, but I’m more grateful to the other Gen Xers and Millennials who are expanding the conversation to support queer kids, whether their own or are raising kids who are allies.

We still have work to do, though, because many trans and nonbinary kids are still asking if someone is there to help. We need to show them we’re here.

Amber Leventry is a queer, nonbinary writer and advocate. They live in Vermont and have three kids. Amber’s writing appears in many places including The Washington Post, Romper, Grown and Flown, Longreads, The Temper, and Parents. Follow them on Twitter and Instagram @amberleventry and reach out to hire them for speaking engagements and LGBTQIA+ training sessions.

This article was originally published on