With Another Brain-Eating Amoeba Case In The News, Here’s What Parents Should Know

Thinking of going for a swim in that nearby lake? Take some precautions to keep everyone safe.

It seems to be a headline popping up more and more lately: A child has died after contracting brain-eating amoeba. This week, that tragedy took place in Nebraska after a young boy went swimming in a local river. If it's making you question your end-of-summer plans, you surely aren't alone. After all, for many families, squeezing out every last drop of summer entails so much swimming that little fingers and toes remain in a near-perpetual state of pruney-ness. If you don't live near a beach, the "body of water" you frequent is probably a local freshwater pond, river, or lake. And there's absolutely nothing wrong with lake swimming — it often feels like a wonderfully nostalgic summer activity. However, as the air heats up, so does the water. When that happens, the conditions can become perfect for the emergence of brain-eating amoeba.

Before you panic and cancel your annual trip to the lake house, take note: The chances of contracting brain-eating amoeba are still very rare. It is, however, almost always deadly. So, the best thing you can do is arm yourself with knowledge and be as prepared as possible (a mother's motto!). So, what is brain-eating amoeba, exactly, and where is it found? What are the symptoms? And most importantly, how can you avoid brain-eating amoeba altogether? To answer these questions, Scary Mommy turned to health experts to find out what parents should know.

What is "brain-eating amoeba" or Naegleria fowleri?

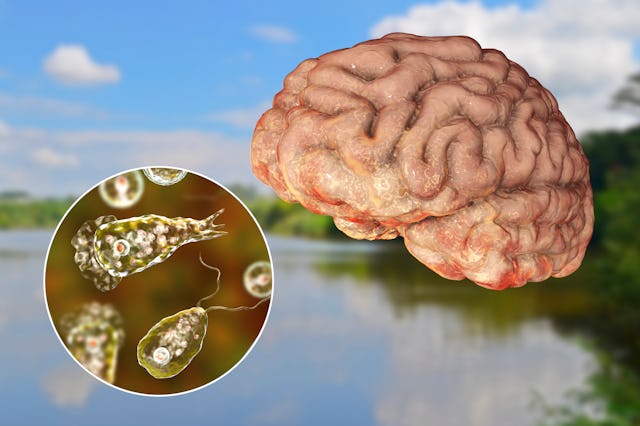

“Naegleria fowleri is an amoeba that lives in warm freshwater and can infect a human when water containing the amoeba goes up the nose. Infection does not occur by other contact with water, including drinking water," explains David Culpepper, MD, Clinical Director of LifeMD.

Ryan Kaczka, a Board Member with ChoicePoint Health and a Senior Public Health Advisor, elaborates, "A type of amoeba known as the 'brain-eating amoeba' was identified in 1965 ... it typically hides out in warm freshwater areas or dirty, untreated waterways. When it enters the human body, it creates a lethal infection and inflammation in the brain that ultimately results in the 'eating' away of brain tissue. The medical term for [the condition it causes] is primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM)."

Where can brain-eating amoeba be found?

According to a press release from Nebraska's Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), this brain-eating amoeba is most commonly found in lakes, rivers, canals, and ponds throughout the United States. However, it's not found in every body of freshwater — brain-eating amoeba thrives in warm conditions.

"Since it thrives in warm water, Naegleria fowleri is often associated with summertime recreational activities, such as swimming in rivers and lakes. Much more rarely, infection can take place in swimming pools that are not adequately chlorinated," explains Culpepper. "Though in the U.S., Naegleria fowleri has most often been associated with the Southern states due to their warmer water temperatures, more recently there have been cases further north, possibly due to climate change."

Because the amoeba can grow in any warm freshwater, it has also been linked (very rarely) to tap or faucet water going up the nose, according to the CDC.

How common are brain-eating amoeba infections?

Still extremely rare. "Although N. fowleri amoebas are rather abundant, brian damage is seldom caused by it. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis due to N. fowleri happens somewhere from 0 to 8 times a year, nearly always between July and September," says Kaczka, pointing out that there have been 154 confirmed cases in the U.S. from 1962 to 2021 (four of those people survived).

How can you avoid brain-eating amoeba?

Naegleria fowleri can only enter your body through the nose. You cannot get it from person-to-person contact. Nor can you get it from drinking the water. (Ew, David.) It enters the body through the nose and then makes its way to your brain, where it does its damage.

To that end, there are a few things you can do to help safeguard your family:

- Avoid freshwater swims altogether during the warmest months.

- If you do swim in freshwater during those months, use nose plugs.

- As tough as it can be, do your best to keep your kids away from puddles and other warm and/or dirty water.

- Avoid any activity in warm freshwater that is more likely to forcefully push water up the nose, like jumping, diving, tubing, skiing, and other water sports.

- Try not to dig or stir up the sediment at the bottom of freshwater bodies of water.

What are the symptoms of a brain-eating amoeba infection?

If your family has recently taken the plunge into some freshwater and now you're feeling panicky, remember that it's a very rare condition. According to the CDC, there have only been 31 cases in the last 10 years. You're probably fine. However, there are symptoms to look out for when worried about brain-eating amoeba. Initial symptoms usually start around five days after infection. Symptoms progress rapidly from there, usually resulting in death within about five days.

Initial Symptoms:

- Headache

- Fever

- Nausea/Vomiting

Later Symptoms:

- Stiff neck

- Confusion

- Lack of attention to people and surroundings

- Loss of balance

- Seizures

- Hallucinations

All of this to say, be smart but remember — you can't live in a bubble. In the very rare event you've been swimming in freshwater and notice symptoms that seem consistent with a brain-eating amoeba infection, seek emergency medical care as soon as possible. Otherwise, just take practical precautions. Advises Culpepper, "Though infection from Naegleria fowleri is still extremely rare, those who worry about infection can avoid swimming in warm freshwater areas and under-chlorinated swimming pools."

This article was originally published on